Sequences, series, convergence

The variables

Sequences

A sequence is precisely defined as the map $f:\mathbb{N}\rightarrow X$ from the natural numbers to some infinite cardinality set.

\((x_n)_{n\in\mathbb{N}} = \{x_1, x_2, x_3, \cdots\}\) where $x_1 = f(1)$, $x_2= f(2)$, and so on. It’s kind of freaky to think of the sequence as being the function itself and not the set, but conceptualizing it this way helps when we characterize functions themselves as sequences. (We’ll get there. Hopefully before my final tomorrow.)

I didn’t grasp that they were truly infinite for much longer than I’d like to admit, but it makes sense also from the perspective that maps (functions) must map each element in the domain to some element in the range. So every natural number in $\mathbb{N}$ (a countably infinite set) must be accounted for.

Partial sums

A partial sum is, as the name implies, a sum of all the values in the sequence from 0, up to a certain (‘partial’ not infinite) truncated point.

\[\sum_{n=0}^N a_n = a_0 + a_1 + \cdots a_N\]I was intimidated by the notation and the concept of a partial sum for so long (recall: the PDE incident) but honestly it’s not too bad. Although I do say this after having the notation bashed into me from learning the YIN algorithm.

Series

We define a series as being the sum of ALL terms in the infinite sequence. So the partial sum is able to graduate to becoming like an ‘infinite sum’ in the sense that it becomes a series.

\[\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n\]Convergence?

Convergence is when we study what happens as the sequence or series approaches infinity. To put it back in the map terms (lol), as the domain of the map grows to infinity, then we want to know what happens to the values in the range set of our map.

Convergent sequences

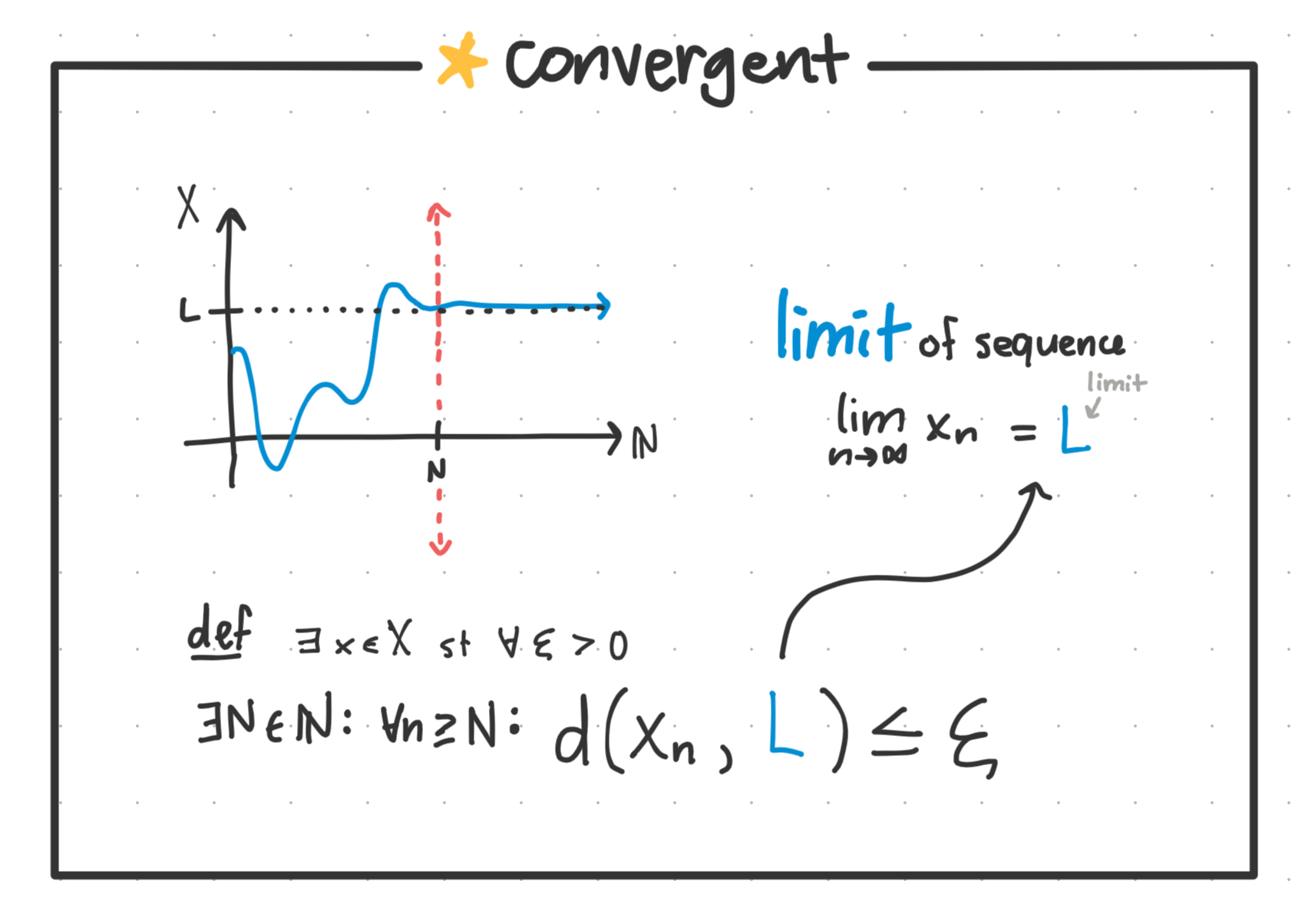

Precisely, we define a convergent sequence as being one where the limit of the sequence exists.

- Which means, there exists some point, some $N \in \mathbb{N}$ such that for all $n$ after that point, the distance between the the sequence $f(x)$ at that point and some limit $L$ is less than $\varepsilon$ for all $\varepsilon>0$ . If so, we say the sequence converges to $L$.

- So, we know a sequence converges if it satisfies the above definition, as in, all values beyond a certain point are epsilon-close to some limit $L$.

If you squint at the picture, it looks kind of like if the “function” mapping $\mathbb{N} \rightarrow X$ converges on some $L$ (horizontal asymptote).

We don’t care what happens in the beginning - it could be doing some crazy shit and as long as it converges toward some limit L then we consider it convergent to that number.

A divergent sequence is simply one that doesn’t converge.

Series convergence

For series, we have three kinds of convergence.

- Convergence

- Absolute convergence

- Conditional convergence

Series convergence is about trying to find some limit sum $S$ which the infinite sum is approaching.

\(\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty}\sum_{i=0}^{n} a_i = S\) We can reuse the same limit notation and describe the sequence of partial sums instead, and say that the series $\sum a_n$ converges if the sequence of partial sums ${s_0, s_1, \cdots s_n}$ converges to some $S$ as $n \rightarrow \infty$. Hence, all the partial sums beyond a certain point $N \in \mathbb{N}$ are within $\varepsilon$-distance from $S$.

Absolute / conditional convergence

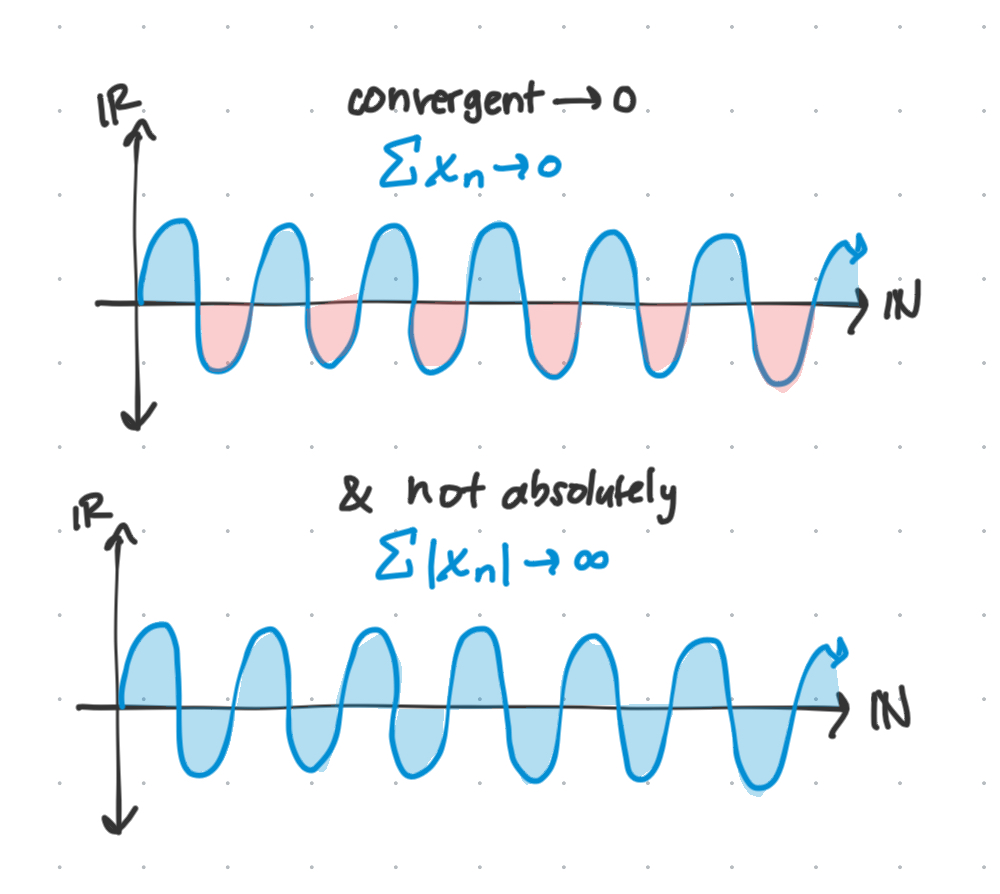

However, a series can still ‘converge’ even though it doesn’t look like the area approaches 0.

This is where the second and third kinds of convergence come into play.

A series converges absolutely if the absolute value of each value in the sequence creates a partial sum sequence which converges. It’s a stronger version of normal convergence.

\[\lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}\sum_{i=0}^{n}|a_i| = S\]An obvious property of absolute convergence is that it implies convergence.

- The proof is short, and comes from using the triangle inequality to break apart the absolute value of the normal convergent series into an absolutely convergent variant of the seres.

If a series converges but not absolutely, we call it conditionally convergent.

Series convergence tests

A more involved question is, how do we know if a series converges?

Cauchy Criterion for Series Convergence

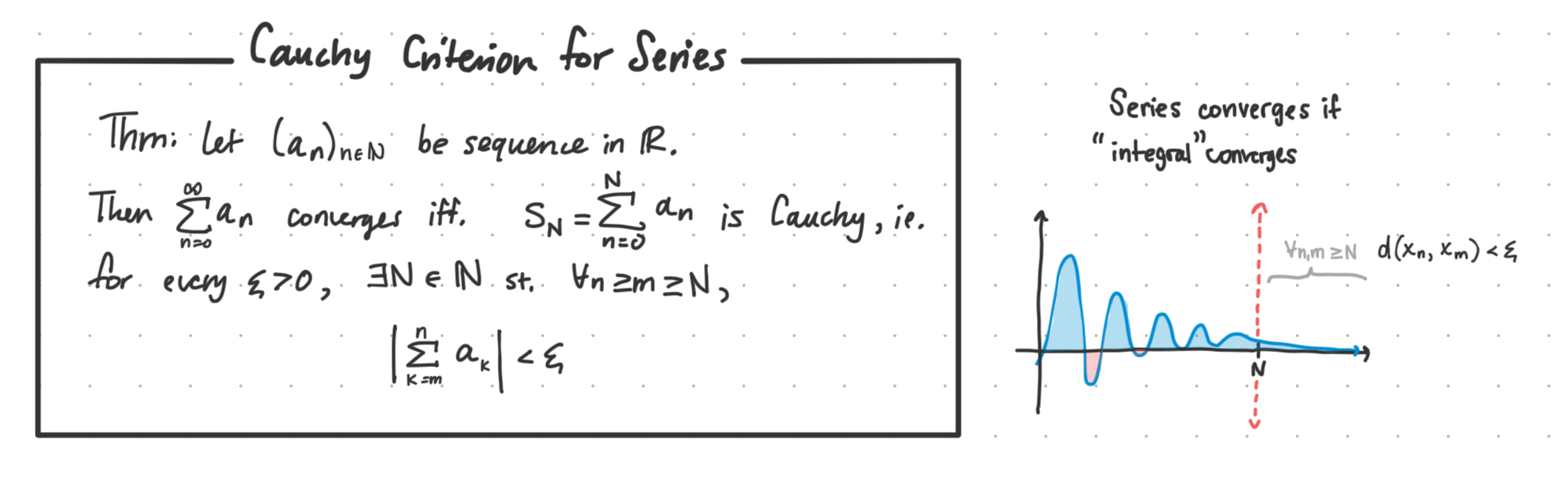

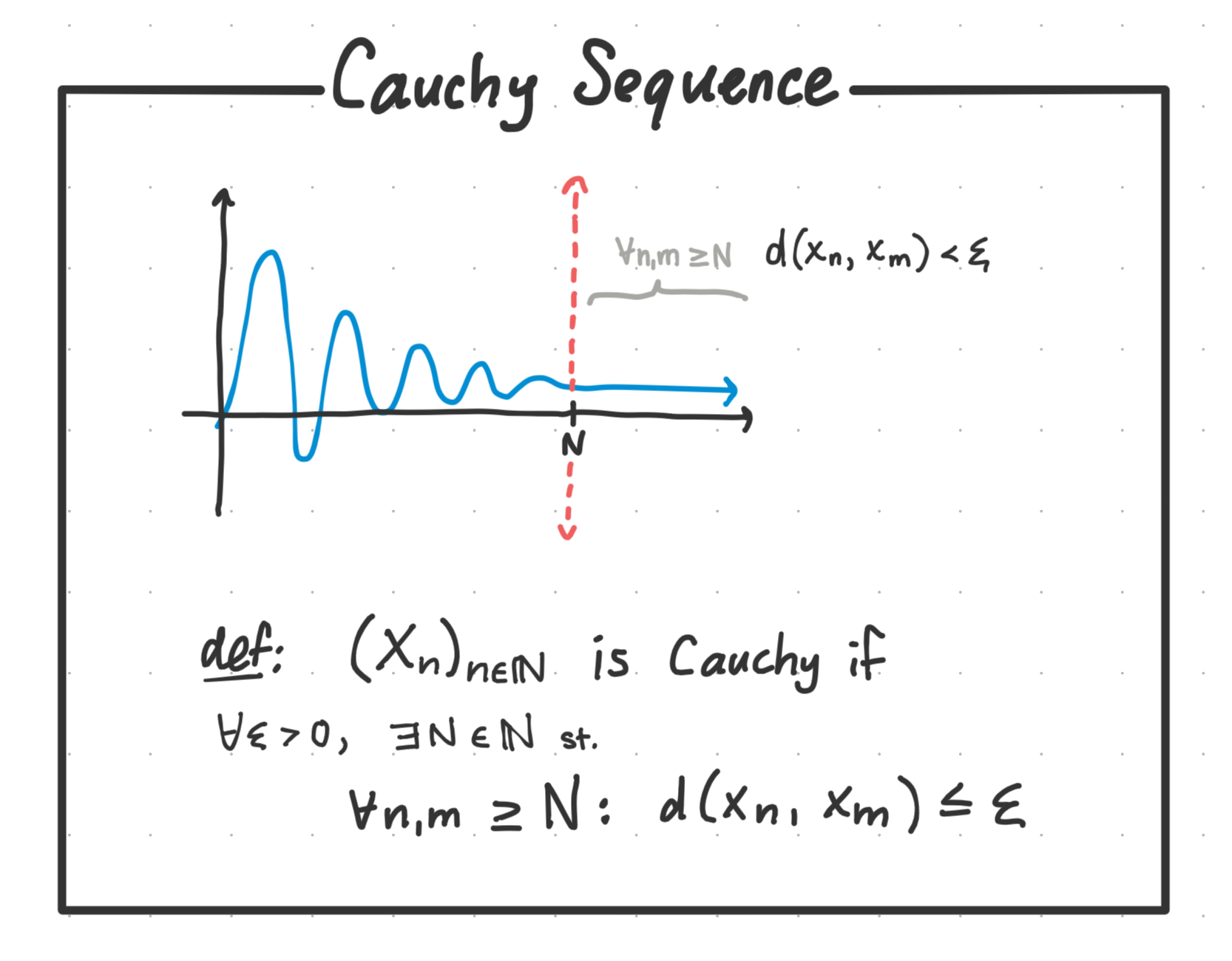

One test uses the idea of a cauchy sequence and if the series is cauchy then we know it converges (Cauchy Criterion). In order to explain this let’s unpack what is a cauchy sequence.

We can intuit that this must mean that the successive sums must start approaching zero at some point. The constant series $\sum (a_n)_{n\in\mathbb{N}}=1$ for instance diverges because we’re adding $1$ to itself infinitely many times.

So at some point these partial sums gotta approach zero.

This leads us to the concept of the Cauchy Criterion for Series Convergence, which states just exactly that.

It was when I was staring at this Cauchy criterion for series convergence when I realized you could think of series convergence as being a kind of ‘integral convergence’ where if the area under the discrete sequence curve approaches some constant sum $S$, then the series converges. Which visually must happen if after a certain point the area under the curve approaches 0.

Comparison test

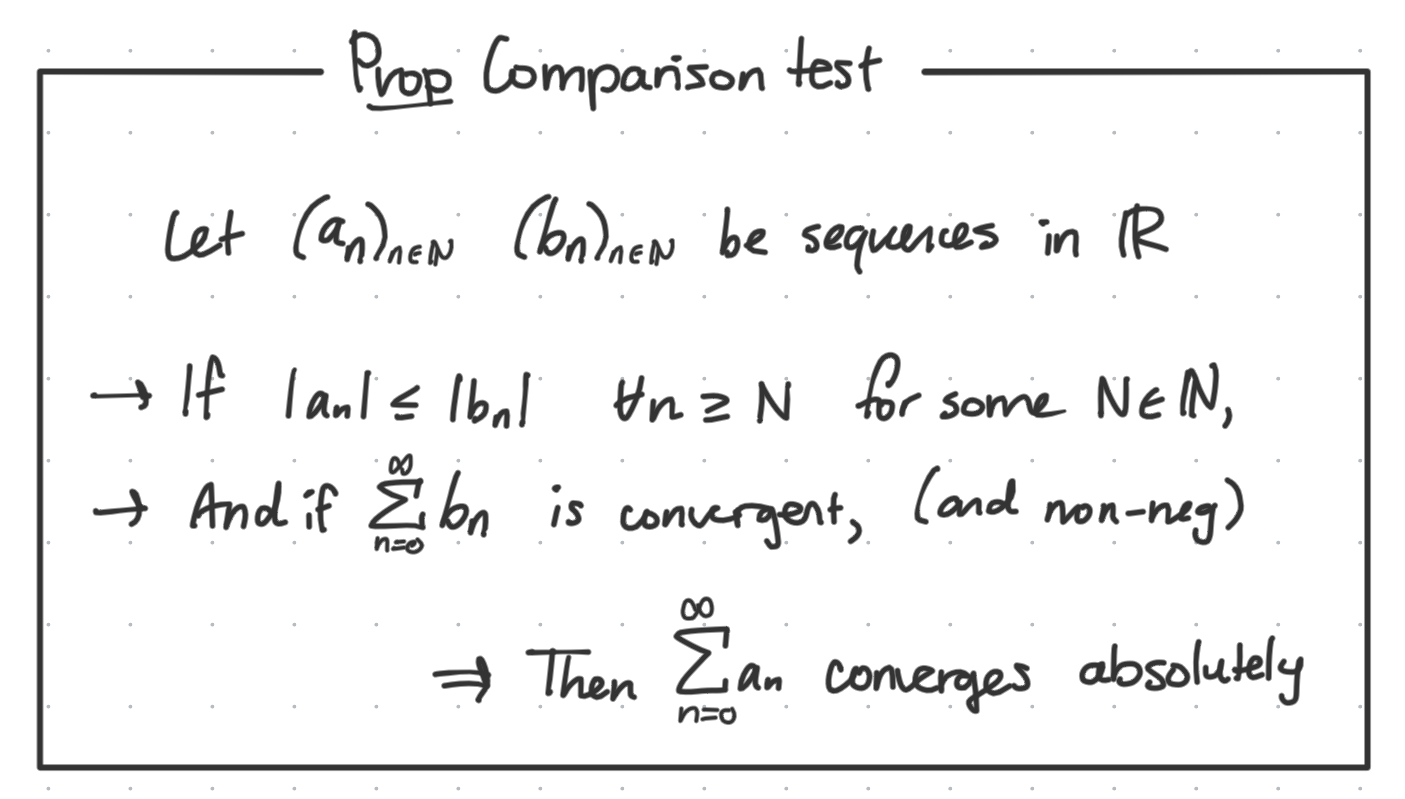

We can compare series we already know converge or not to our series of interest.

If every value of $a_n$ is less than $b_n$ for all $n$ beyond a certain $N \in \mathbb{N}$,

If the end behavior of a_n is bounded element-wise by a convergent sequence, then a_n also converges absolutely.

Ratio Test

If the absolute ratio between the next successive element over the current element is less than 1, then we can say it converges absolutely.

\(\limsup_{n \rightarrow \infty} \left | \frac{a_n + 1}{a_n} \right | < 1\) The cases are:

- Ratio $< 1 \implies a_n$ converges

- Ratio $> 1 \implies a_n$ diverges

- Ratio $= 1$ is inconclusive

This notion is analogous to how a geometric series $\sum^\infty a^n$ converges if $a < 1$, and is exactly the test we can use to prove it.

We use the notion of the $\limsup$ to say that we only care about the ratio as $n$ grows infinitely large. The ratio doesn’t matter in the beginning as long as it eventually, with some infinite number of terms, approaches our desired ratio.

Root test

If we take the infinite root of the sequence as it approaches the end and this root is less than one, we say the series converges.

\(L = \limsup_{n\rightarrow \infty} \sqrt[n]{|a_n|}\) The cases are:

- $L < 1 \implies a_n$ converges

- $L > 1 \implies a_n$ diverges

- $L = 1$ is inconclusive

This one still doesn’t make much intuitive sense to me, but it’s okay since I have 3 other tests I can use in it’s place for now.

Cauchy sequences

A cauchy sequence is one whose values stay somewhat close to each other after a certain point.

Precisely, beyond some $N \in \mathbb{N}$, the distance between any two sequence values with $f(x)$ larger than $N$ must be smaller than $\varepsilon$.

All convergent sequences are cauchy!

When we look at the cauchy sequence, it looks pretty similar to a convergent sequence.

The distinction comes from the fact that cauchy sequences only have to be epsilon-close to values within itself.

But not all cauchy sequences converge…

However if the space is not complete - ie, there are holes - then it may want to ‘converge’ onto a hole that doesn’t exist in the space.

For example, take the sequence $(x_n)_{n\in \mathbb{N}} = \frac{1}{n}$ in the space $\mathbb{R} \setminus {0}$. Then as we approach infinity, the sequence would be cauchy any two values can be $\varepsilon$ close to each other. However there is no one value in the space that we can say it approaches, because it always gets closer and closer to something that doesn’t exist within the space.

And in fact, this is how we define what our definition of a complete metric space is, is the space where every cauchy sequence converges.

Result

Tl;dr it’s good to know that in $\mathbb{R}$ if a sequence is cauchy $\iff$ it is convergent.