Visualizing combinatorics with trees

In all counting problems, we have some $n$ number of items and we want to choose some $k$ of them. There are two fundamental tools for computing this - permutations and combinations, each coming in either with / without replacement variants.

Permutations

With permutations, order matters. What does this mean?

With replacement

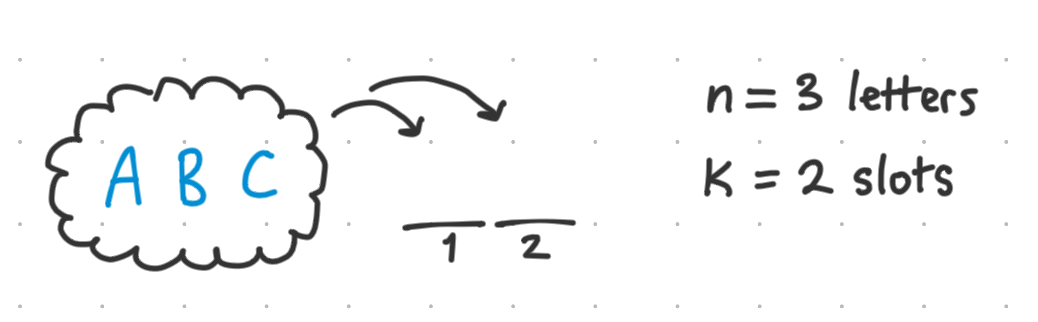

Say we have the first 3 letters of the alphabet ABC. How many unique words (they can be nonsensical) can we create using exactly 2 of these letters?

So we have 2 ‘slots’ and 3 ‘elements’ to choose from.

We can visualize the number of possibilities with a tree.

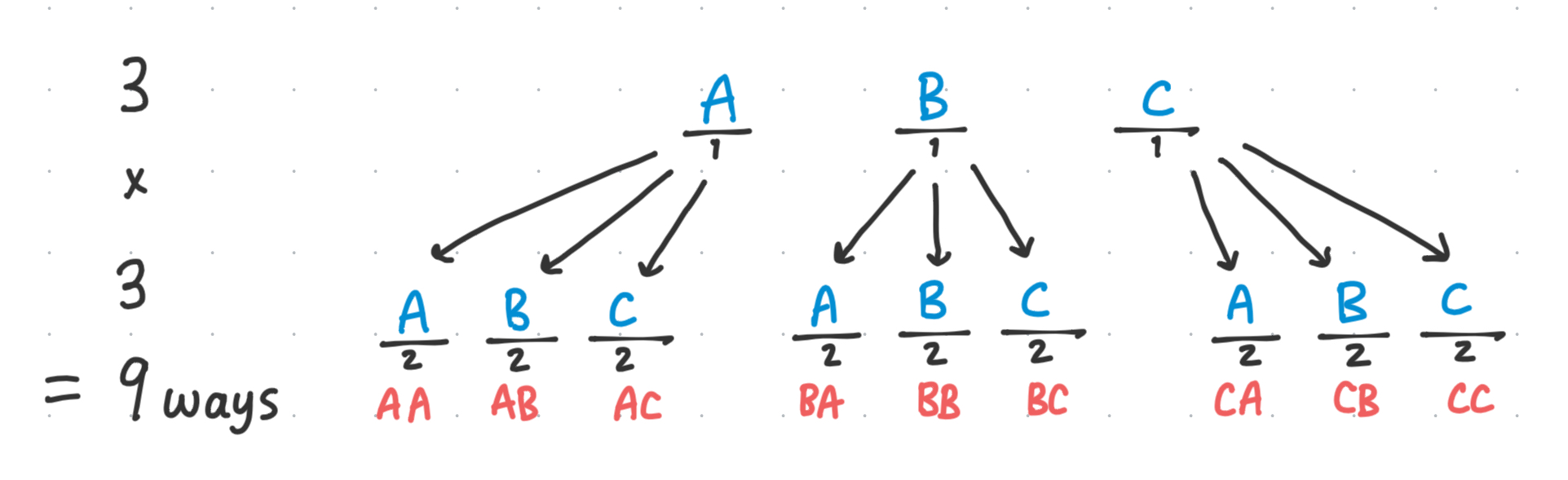

For each ‘slot’, we have 3 different options of letters.

So for each of our 3 letters that we could choose to put in slot 1, we can count another 3 possibilities corresponding to the different 3 letters we could choose to put in option 2. \(3 \cdot 3 = 9 \text{ words}\) (“Word” being a generous interpretation of these 2-letter toy examples)

We call this a permutation with replacement, and hence the formula multiplies the unique number of ways each slot can be combined together. Hence, we multiply the $n$ possible choices by itself, $k$ number of times. \(n \cdot n \cdots n = (n)^k\) Formally, I learned the idea of counting the total number of ways by multiplying the number of ways together as the multiplication principle in my Discrete Math class. But I think the principle is best explained with a tree.

Without replacement

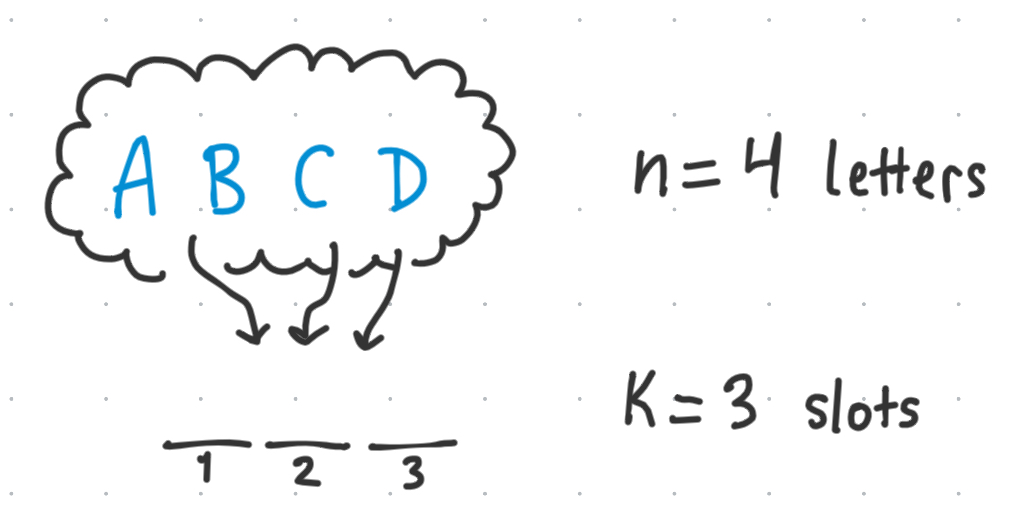

Now, let’s say we have n=4 letters to choose from, and we want to create as many 3 letter words as we can from them, BUT we cannot use the same letter more than once.

This is a permutation without replacement problem, as we are ‘not replacing’ the letters after we stick them into a slot.

This can also be visualized with a tree!

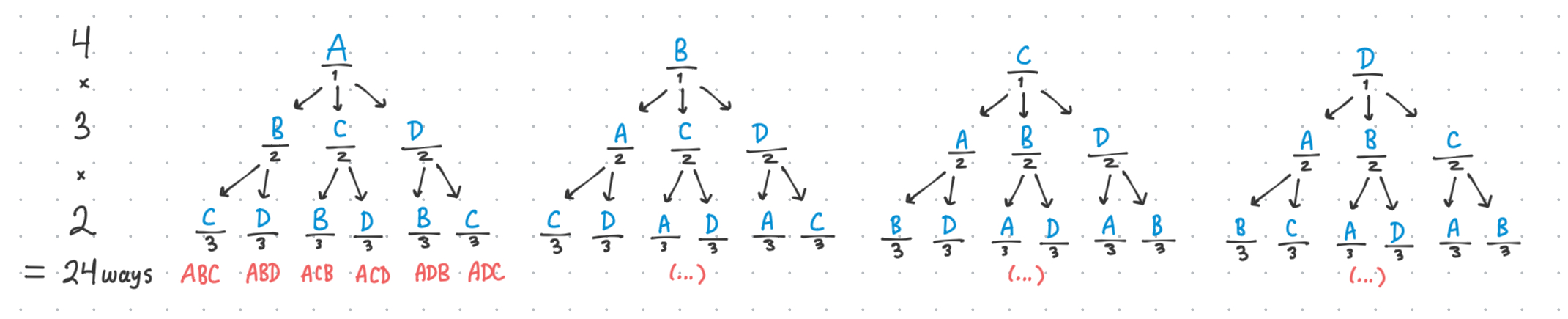

Once we choose one of the 4 letters to place into slot 1, now we only have 3 letters to choose from for slot 2, and so on. So the tree becomes smaller at each branch.

So we take \(4 \text{ ways } \cdot 3 \text{ ways } \cdot 2 \text{ ways } = 24 \text{ total words }\) which is equivalent to taking $4!$ and dividing out the $1$ part with a $1!$ on the bottom. (Sorry this example has a trivial denominator… but you can imagine that if we cut off the tree after the second layer for instance, we would get $\frac{4!}{2!}$)

Note that while we are ‘reducing’ the number of possibilities with each successive slot, that the permutation is agnostic to which order we choose the letters in, as the first layer accounts for all possibilities of letter 1’s, and the second layer accounts for all possibilities of letter 2’s given that particular choice of letter 1, and so on.

Hence the formula is: \(P(n,r) = {}_n P_r = \frac{n!}{(n-r)!}\)

This is also a situation in which I think the notation is a formality which obfuscates the meaning of what the formula is trying to say. Really, we just reduce the number of options by 1 every time we choose it out of existence, and we only multiply the decreasing $n$ numerator by the number of slots we have.

In class we only learned the formula and received the explanation without an accompanying visual, and it made me sad to hear some of my classmates recalling / using permutations only by this formula, but missing completely the intuition behind it. I think understanding the derivation enables me to better remember and apply a combinatoric mindset to a wider array of problems.

Thinking about permutations (and counting problems in general) with trees has helped me connect the formula to the physical intuition of ‘counting’ in a way that has helped me conceptualize harder problems as well.

Combinations

Combinations differ from permutations in that we are choosing $k$ elements where order does not matter.

Without replacement

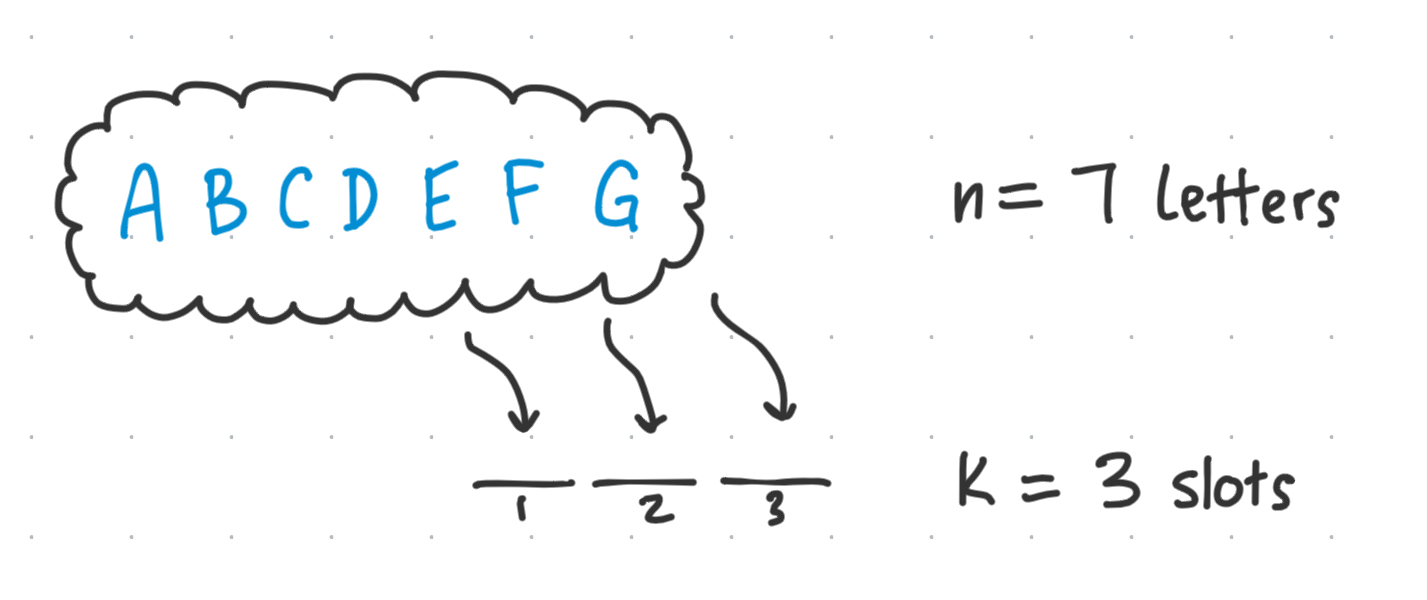

Say we have the first 7 letters of the alphabet and we want to count how many unique combinations of 3 letters we can create using them, where order does not matter.

If we treat it first as a permutation, then we could assume we have 7 choices for the first slot, 6 choices for the second slot, and 5 choices for the third slot.

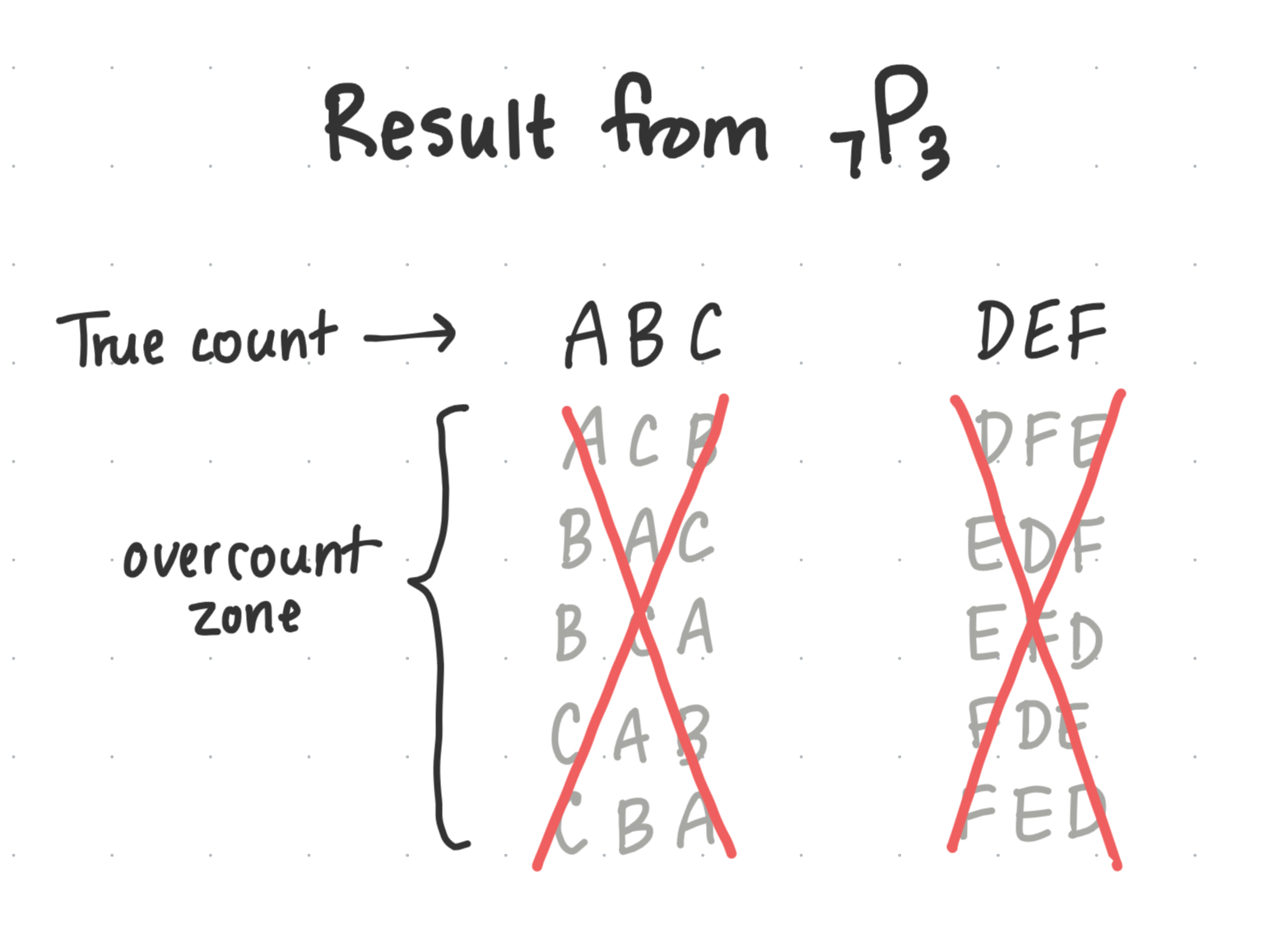

However, in doing so we end up overcounting all the cases where we have the same 3 letters but in different orders.

How do we go from a result that overcounts by so much to the true result?

We can observe that the factor by which the permutation overcounts is just the number of ways you can order 3 things in 3 spots. We want to count one of those, and ignore the rest.

So why not just divide out the naive permutation result by the number of ways we can order (permute) 3 items in 3 slots?

And indeed that is the formula for combinations without replacement!

\[C(n,k) = \binom nk = \frac{{}_n P_k}{{}_k P_k} = \frac{n!}{(n-k)! \cdot k!}\]Something which weirdly helped me understand it better is to think of the combination as a number, such that: \({}_n P_k = \binom nk \cdot {}_k P_k\) Which is a little strange but helped it click in my mind, especially combined with crossing out the overcounted permutations.

With replacement

The final type of counting problem I’ll go over in this post is the combination with replacement, which requires a different way of looking at the problem than the previous methods.

(to be finished later, once I find the motivation)

Leave a comment