Presentations; Group problem solving

Group meetings: Overview

Every Friday, Gang lab holds a group meeting from 10am-12pm where 1-2 lab members present on the progress they’ve made on their projects. The presentations generally include a lot of experimental results and microscope images of the DNA origami crystals.

My labmates are some of the most down-to-earth, yet secretly cracked people ever. At the beginning of their presentations, Dr. Gang will be like - “Today, Dan will be presenting. By the way, congrats on getting your paper into Science.” And then they’ll present like 45 minutes of crushing DNA superlattices, creating DNA sequence libraries, attaching linkers to the octahedra - and end with pictures of their cats, dogs, or other snippets of personality into their final slide.

One memorable such moment was when Elad concluded his presentation with some potential notebook designs to give to the lab. When we asked him what the middle notebook was, he said that it was clearly, “DNA superlattices falling on Manhattan.”

We are unfortunately only imagining what they would look like since we ran into some issues with the printing company.

My turn!

Today, it was my turn to present on my coloring algorithm project.

They didn’t tell me anything specific they wanted to see - so I decided that since I don’t have any kind of experimental results to share with the algorithm, that it would be nice to explain the algorithm itself and to treat it like a 1hr mini-lecture teaching the rest of the lab on how this fundamental algorithm works.

I’ve attached the actual presentation for anyone who’s curious to skim through.

![[Presentation1.pdf]]

Creating the presentation

I completed the bulk of the presentation the night before—apparently, a rite of passage in the lab. I thought back to how Eric (a labmate) confessed after his own presentation that he hadn’t slept at all the previous night, which made me feel better about my own frantic finishing touches as people trickled into the room. I connected my computer to the projector running on 2 hours of sleep and 600 mg of caffeine.

The presentation: Introduction

Who am I?

I began my presentation with a “Who am I” slide.

(Not a very pretty slide 💀 - if I had time, I would’ve added a picture of either me, Jason, or both.)

It’s interesting because I sometimes wonder why is it customary to start presentations with a “Who am I”? slide. After all, almost everyone in the lab already knew who I was.

I think back to my 11th grade AP Lang class, where we talked about “establishing ethos.” Which is to say it helps prime the listeners for why they should listen to what you’re saying, and believe you. To be honest, I still think it’s done mostly out of custom more than anything. But I included it anyways.

Motivation, roadmap

Next, I outlined the motivation behind my research and the roadmap for the talk. I wanted the motivation to answer the question of “why should I care?” for the listener.

And the roadmap is a particularly important conceptual tool not just for presentations but for problem-solving in general. I wanted to prime the reader for the high level content structure of the presentation, to provide a context for which the details could slot into.

My initial roadmap looked like this:

- User interface

- Data structures

- lattice, surroundings, symmetries

- Algorithms

- Bond panting

- Post processing

- Future directions

While this was my intended roadmap, the presentation ended up unfolding in a completely different way.

The presentation: Group problem solving

My biggest takeaway from presenting was that people do not remember definitions, and that good presentations / teaching is about group problem solving.

I planned to start with the user interface, thinking it was the most relevant part for lab members who didn’t care about the details and just wanted to know how to use the code.

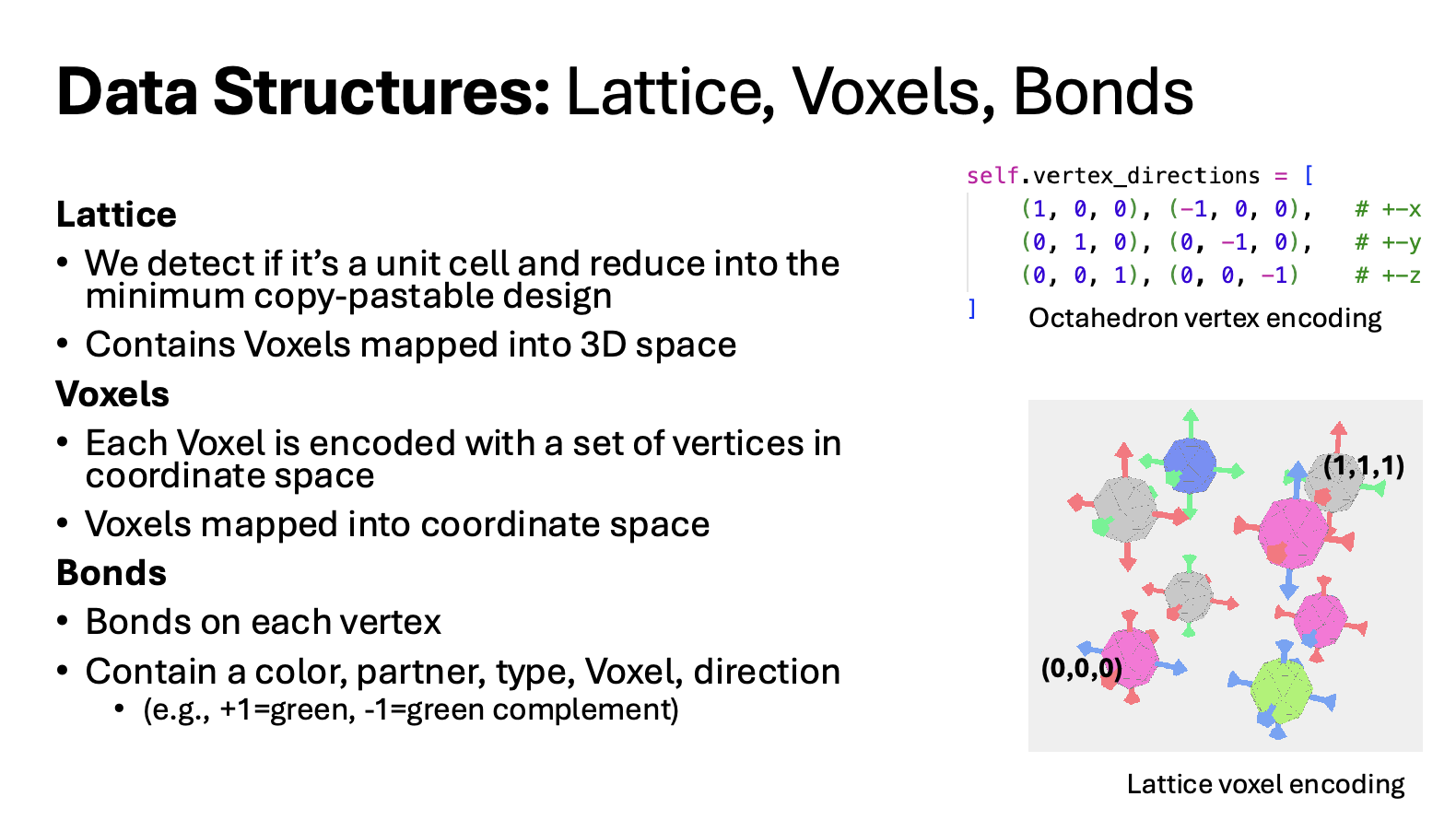

And then I would go on to explain how the lattice itself is encoded in the code, how we compute a “symmetry operation,” then dive into the painting algorithm itself. I feared that otherwise, if I tried to explain the painting algorithm without explaining these definitions, then they would be confused what I was talking about.

Starting from the example

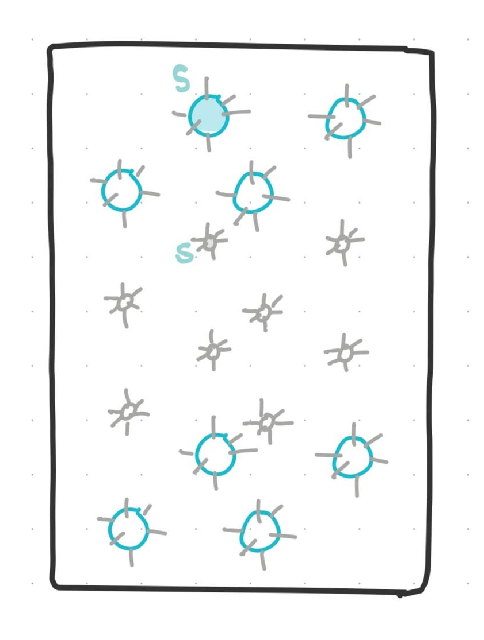

However, I was surprised when in the end, I ended up spending 60% of the presentation on one slide - at the very end, containing a single example picture:

As I started presenting, I realized I needed a way to explain what a “Voxel” and a “Bond” in a way that everyone could understand. And to explain how the mapping actually worked. So I jumped to like my third-to-last slide (at the time) which contained the above example.

Instead of having the user walk through a slide like this (my original slide):

I found that just using the example slide and pointing - “this is a voxel”, “this is a bond”,” this is the lattice”, “this is the minimum copy-pastable design” - that was way more effective than trying to explain it in this kind of isolated slide.

I was happy to hear my labmates asking clarifying questions. They would stop and ask - “So just to be clear the minimum design is the thing inside the square?” “The structural voxels are these two?” “A symmetry is the rotation of the surroundings?” In the end, most of the content of my presentation flowed just from sitting on the example slide, and working through how we would color the lattice manually, following the algorithm step by step, and addressing the concepts of symmetry operations, types of painting operations, structural voxels, complementary voxels, etc., not in their isolated slides, but rather as they naturally came up in our group discussion of how we are trying to paint this lattice.

Why was presenting it as a problem more effective? I think it’s because it enables lets you easily tie new concepts and definitions back to the main idea - that we want to color the bonds. I realized that my original idea, of just showing the slide of data structures, gives people a bunch of information without saying much about why it matters or how it’s used. In contrast, by staying on the example slide and walking through the problem step-by-step, my labmates could remember the context in which the structural voxels, the symmetries, these random definitions - what context they mattered in. Because posing it as a problem prompts the listener to think about how they would solve the problem themselves, and then revealing my presentation content - not as arbitrary definition-vomit, but as answers to their natural questions - that this was the most effective way to present the information and keep people engaged.

Aftermath, feedback

After the presentation, my labmates congratulated me saying that it was an interesting presentation, good job, and that they were impressed that I was working on such a difficult problem. It made me really happy to see that

- I’m not going crazy and this stuff is hard

- Now my labmates know that I’m not just goofing around

For a while I felt very out of place, like the work I was doing was just some trivial job given to the undergrad CS major. But it was really rewarding to see everyone interested and asking questions.

Feedback: Expanding motivation, less jargon

I received one piece of feedback - that I should use more low-level definitions whenever possible. Elad (the guy who made the notebook covers) advised me that he would rather I use “DNA sequence” to describe the bonds rather than to abstract them by calling them “colors.” He explained that when I use jargon without explaining, that people don’t always understand what I’m talking about. Also that I should’bve spent more time motivating what is the utility of this algorithm, what do the balls and sticks really mean, what applications are there for this algorithm, etc.

I told Elad that I had skipped over that step - partially because I had ran out of time - but also because I had assumed that the lab was already familiar with the concept of DNA origami and that they would feel insulted or like I’m wasting their time if I spent too long explaining that. Dan McKeen, a good friend also in the lab, agreed with me in saying that I was right to make that assumption; and that there’s no way to make everyone happy. Still, that I can find a middle ground by including more information in the slides for people who want it, and then skip over it or say like a couple sentences / move on if it feels like it’s not necessary anymore.

Concluding thoughts

Overall, giving the presentation was very rewarding and also helped me learn that presenting the topic as a problem to solve alongside the audience is an effective way to teach and present anything in general.

After the presentation was over, I went back to my dorm and slept.