The art of naming variables

The helix problem

Just as I thought I had finally debugged all of the edge cases of the algorithm, last week I went into the lab and was asked to try out the algorithm on this helix design.

Where we can see the a voxel with the neon particle inside of it is spiraling around each layer like a helix, surrounded by empty voxels.

Failure…

The algorithm failed 😂 so I mentally prepared myself for the debugging adventure ahead.

I found myself wanting to give up almost instantly.

- I had absolutely zero intuition on this problem - not even knowing what the final result is supposed to look like.

- And it’s a design which is too hard to write out even by hand.

- There’s so many different steps and points at which the code could have gone wrong, that I don’t even know where to look.

So I decided it might be nice to go through the algorithm sequentially, refactoring the code so it makes sense until I know every corner and edge case that could possibly happen.

Refactoring

A poorly-organized voxel rotating class

I started unpacking some of the 💩 I had written in the past month. The algorithm required frequent voxel rotations and comparisons for symmetry / mapping, so I had decided to create a “VoxelRotater” class which was supposed to deal with everything related to rotating these guys. But looking back, it contained a bunch of random functions not even related to rotating or voxels, was extremely messy, and had no consistent scheme to its member function arguments / return values.

When I went to refactor it, I found there were so many considerations to organizing the code. Should I rotate the voxel, or just the bonds? Should I return just the bonds, or an entirely new voxel? Each voxel is like a node in a huge graph though, so how do I manage references to all the connections and partner-voxels in either case?

How do you keep track of a monstrous codebase?

A quote that’s stuck with me recently is that software engineers spend most of their time reading, rather than writing code.

This was a notion I had not really internalized until I began doing CS research. I found that the act of working on a single codebase and iterating upon it for many months, or years - required an additional set of skills from those of writing those disposable monomer-files of code for class.

After the codebase becomes tens of thousands of lines long spread out across 20+ files, it became incredibly difficult to remember everything across multiple scattered work sessions. Even after writing extensive docstrings and trying to use good OOP practices, it still took me like 30 minutes to an hour to reload this code back into my brain every time I started working. But did it have to be this hard?

The art of naming variables

My code-brain-reloading was being hampered by a poorly-summarized cog in my code - the voxel rotating cog.

I jokingly titled this post the art of naming variables, but it may be more apt to call it the art of quality grouping. What I was missing, was to consider what is the most essential function of this class, such that when future me goes back to look at it, she is able to quickly refamiliarize herself with what’s going on?

A well-organized example

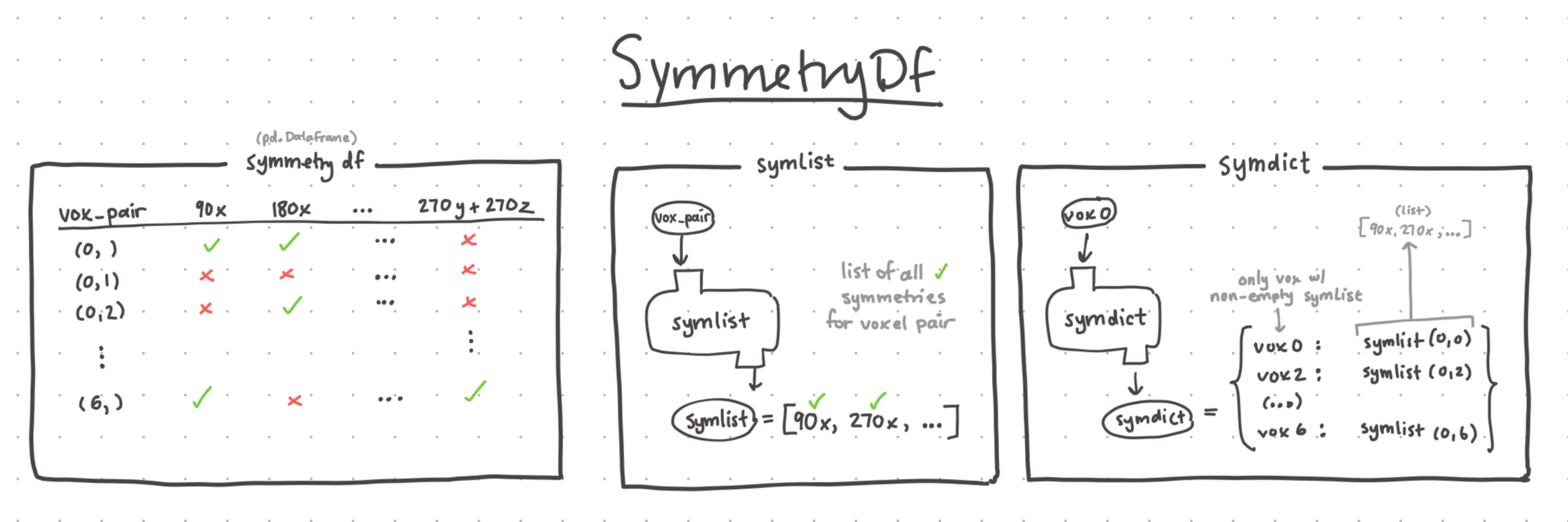

A or example, earlier in the summer, I created this organizational structure for the symmetry operations in the algorithm.

The algorithm needs to regularly query what the symmetry is between two voxels in the lattice. So what these data structures are doing, is essentially computing all pair-wise symmetry combinations between all voxels in the lattice, then storing it in a dataframe. In doing so, each standalone row becomes the ‘symlist’ where we can simply index the dataframe at the key corresponding to our voxel pair, and we can return all the different symmetries between the two voxels.

Creating this organizational structurehas sped up the rest of my coding experience tremendously, as I don’t have to think about all the auxiliary steps in between to compute a symmetry operation between two voxels, but I can just call some easy functions and get exactly what I want. The naming scheme makes sense, so I can just remember to call symlist(v1, v2) instead of reinventing the wheel each time.

Learning from the organization of computer architecture

This problem of organization reminds me of how in my computer architecture class, we could create these very large circuits using just ANDs/ORs (…).

Once we created a functional block of logic gates all centered around a singular function (say, an adder / ALU), we would group it together and start using them not in their full boolean glory, but as a new symbol, which we used to make even more complex circuitry.

I feel like I have a lot to learn from this field - that coding my large codebases in higher level languages is an analogous project, where the quality of what groups we choose to make vastly affect the usability of the group in the end.

The organizing process

So how does one end up on these amazing groups?

Stepping back

I realized I was getting too lost in the weeds of voxel rotation while forgetting the larger algorithmic picture. Stepping back, I wrote out this high level pseudocode:

Algorithm flow

# PHASE 1: STRUCTURAL BOND PAINTING

1. find structural voxels

1. (make all the structural voxels touch each other)

2. paint a path of structural bonds between all structural voxels

3. for each voxel in structural_voxels

1. paint_self_sym(voxel)

# PHASE 2: COMPLEMENTARY BOND PAINTING

while there are unpainted vertices in structural_voxels

1. find an unpainted vertex --> str_voxel + partner_voxel

2. find mesoparent(partner_voxel)

1. if mesoparent is str_voxel and c_voxel

1. map(c_voxel --> partner_voxel)

2. paint_cbond(str_voxel <--> partner_voxel)

3. paint_self_sym(partner_voxel)

4. map(partner_voxel -> c_voxel)

2. elif mesoparent is str_voxel

1. map(str_voxel -> partner_voxel)

2. paint_cbond(str_voxel <--> partner_voxel)

3. paint_self_sym(partner_voxel)

4. complementary_voxels.add (partner_voxel)

3. else

1. map(mesoparent -> partner_voxel)

2. paint_cbond(mesoparent <--> partner_voxel)

3. paint_self_sym(partner_voxel)

4. map(partner_voxel -> str_voxel)

# output: a mesovoxel which should be able to map onto the rest of the lattice

And afterward started to unpack each one and worry about the naming.

I found that this sped up the refactoring tremendously, unifying the different places in which the voxels were being rotated, and giving me a roadmap onto which I could refer back to whenever I would inevitably get lost in the coding sauce.

So did I ever fix the helix problem?

No… I’m still in the process of rewriting everything from scratch to be more intuitive, so I can explain the high level to anyone and they can follow along. Simplifying the code as much as possible, that’s my goal - and then maybe the error in the algorithm will become apparent then.

Leave a comment