Visualizing the string edit algorithm

For my research with Professor Dennis Shasha from NYU, we’re using the string edit algorithm to compare two ‘strings’, user-notes and midi-notes, to return a measure of how accurately the user played whatever piece they were trying to play. I’m writing this blog post to crystallize my understanding of the algorithm, but I hope it helps someone else too.

String editing

String editing is an algorithm which takes two ‘strings’ of ‘letters’ and finds the minimum number of simple operations to transform one into the other.

A string can be defined as any ordered sequence of elements which can be compared to each other. \(S = (l_0, l_1, l_2, \cdots)\)

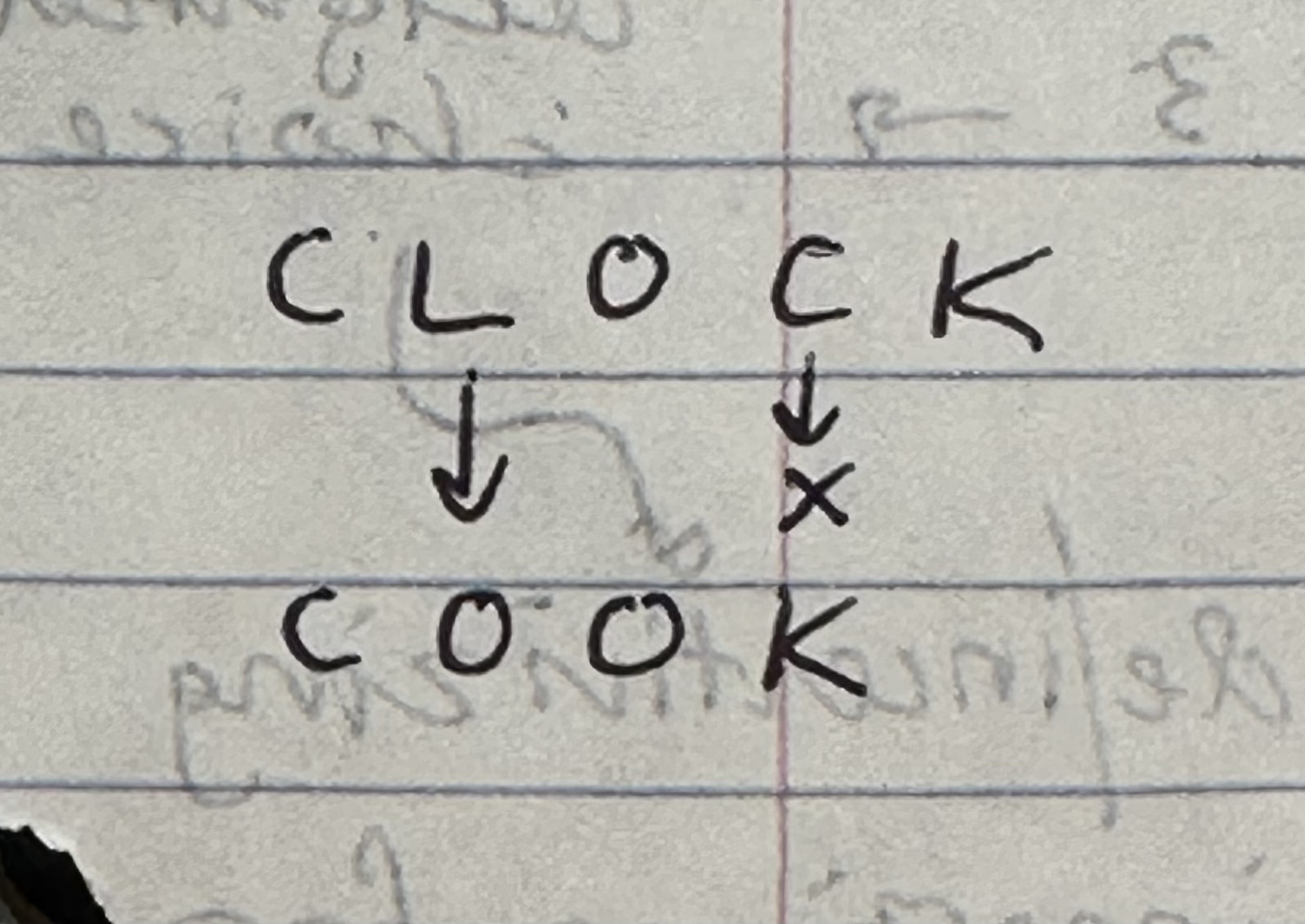

- So like a string could be “COOK” containing the letters in a sequence C, O, O, K.

- Or “CLOCK” containing C, L, O, C, K.

To help us, let’s call user_string as what the user typed, and goal_string as what the desired word is actually supposed to be.

The 4 operations which can help us transform the strings into each other are as follows:

- Insertion: Goal=”C” –> User=”CL” by inserting an “L”

- Deletion: Goal=”OK” –> User=”O” by deleting a “K”

- Replacement: Goal=”CO” –> User=”CL” by replacing “O” with “L”

- No change: Goal=”C” –> User=”C”

Where each operation is defined through what the user did to turn the

goal_stringinto their ownuser_string.- So the operation acts on the

goal_stringand turns it into theuser_string.

- So the operation acts on the

Now given our toolbox of operations, the goal of string editing is to find the minimum number of these operations to transform any goal_string into the user_string. We can think of the 4 operations by considering them in terms of “what needs to happen to the goal string to turn it into what the user actually wrote?” Which reveals the roots of this string edit algorithm in NLP.

How do we do this?

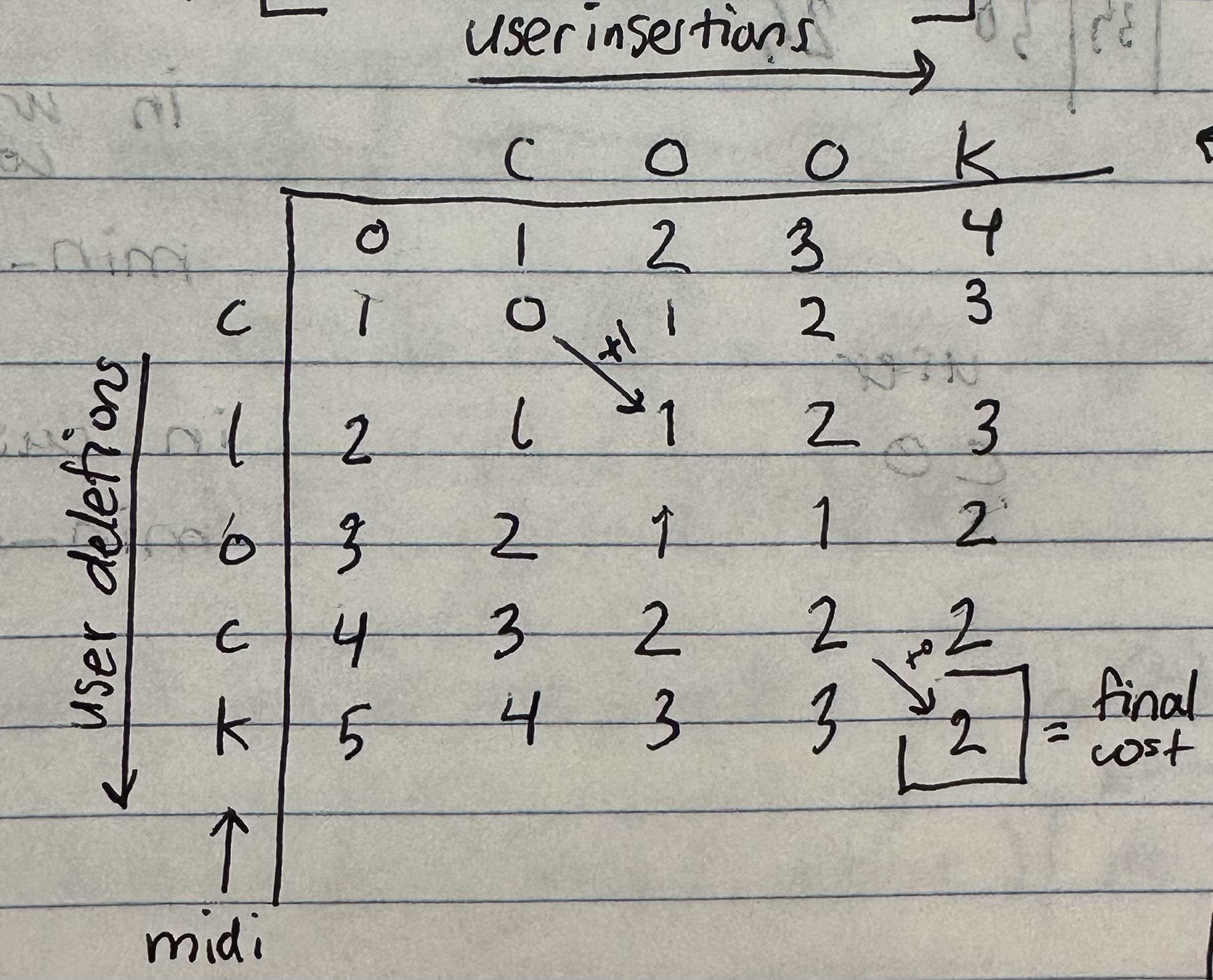

The cost matrix

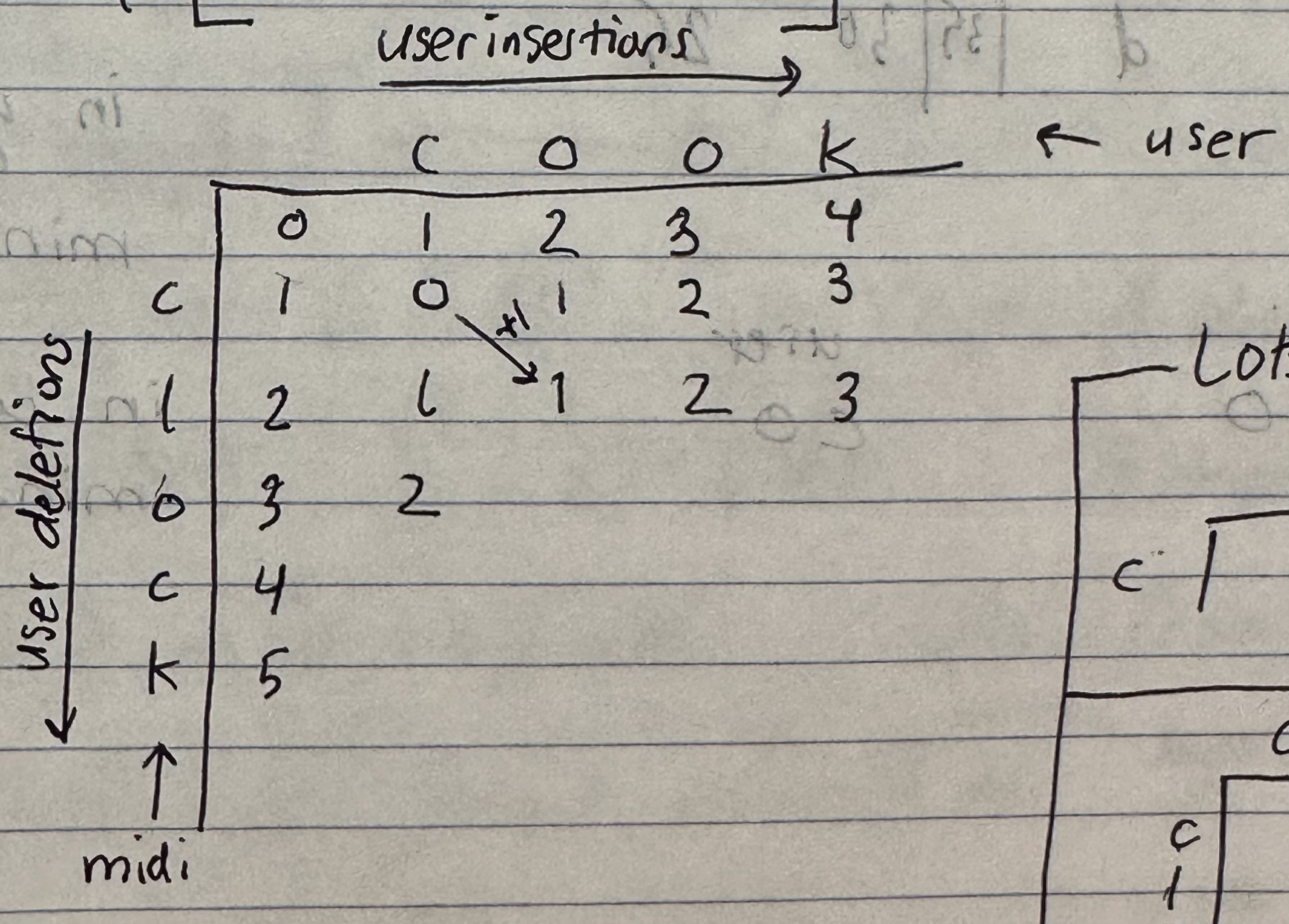

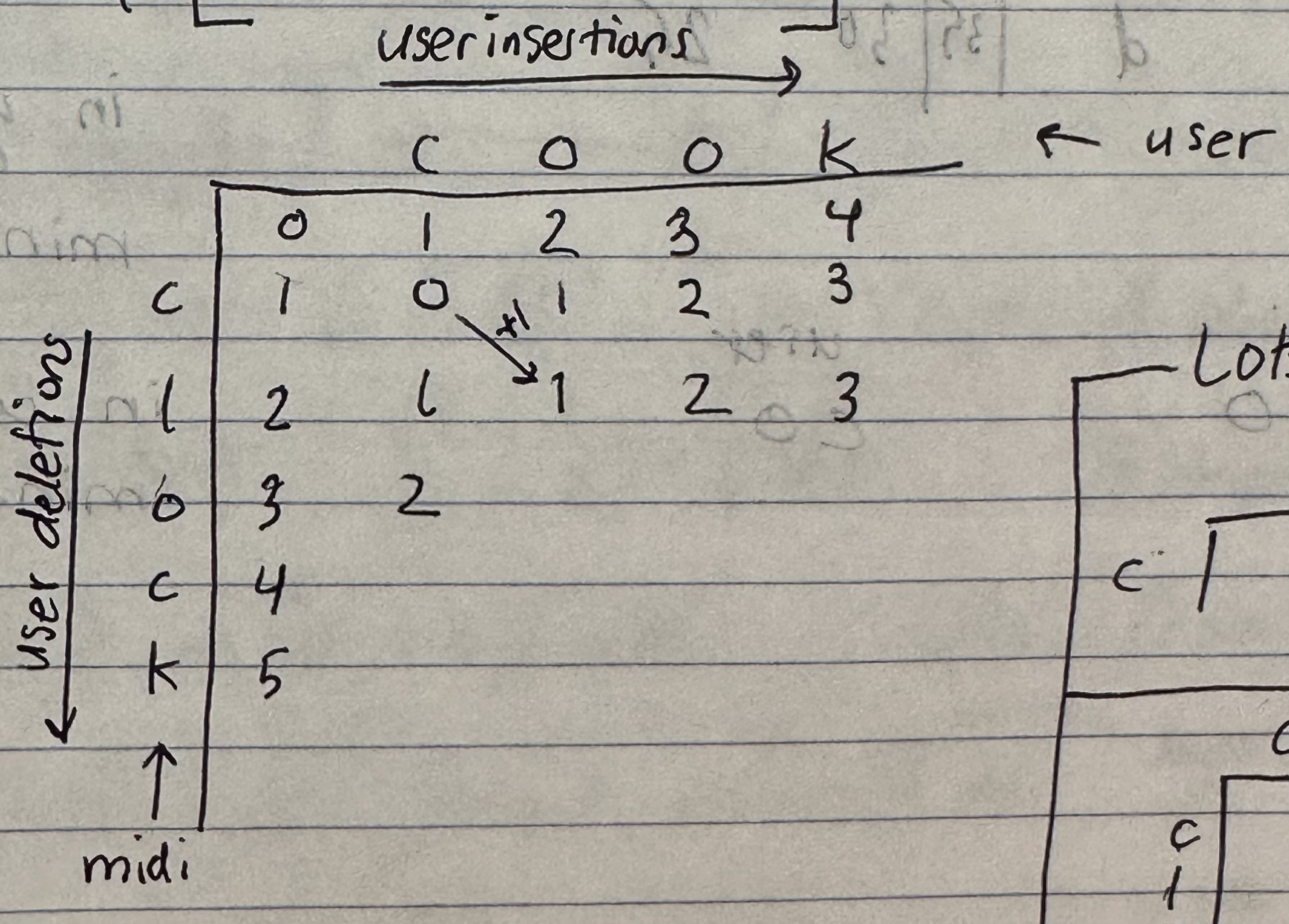

Let’s step back and create a matrix and placing the letters of each string on the columns; the reason why will become apparent once we start computing the costs. Put the user_string on the top, and the goal_string on the left, so that each 2- combination of letters between letters from the two strings is accounted for.

(Ignore the already filled in cells for now)

What goes in the matrix cells?

Each matrix cell corresponds to the minimum cost of finding a string defined by the strings-so-far which correspond to the cell.

- So the

[1, 3]cell returns the cost of transforminggoal_string[:1]intouser_string[:3].

The following two examples helped me motivate the cost determination and how it ties into what is an ‘insertion’ vs ‘deletion’ vs ‘replacement’.

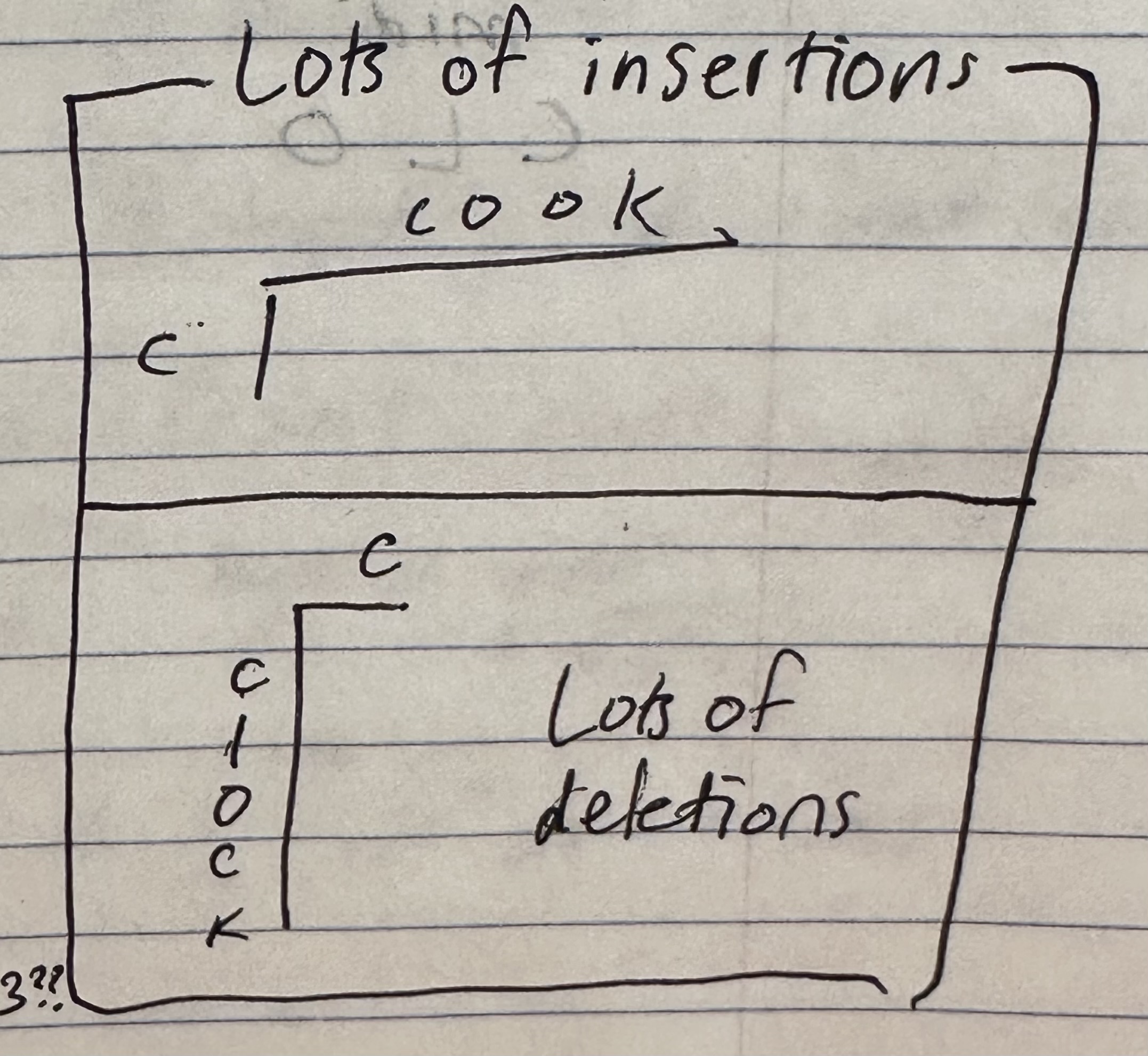

Example 1: Imagine comparing our user string “cook” to the desired string “c”. Then that would return a distance with a lot of insertions.

Example 2: Having a user string “c” and a desired string “clock” would return a distance with a lot of deletions.

How to determine the minimum cost?

Initializing the first row and column

It turns out that if we fill in the first row and column of the matrix with the corresponding values for ‘lots-of-insertions’ and ‘lots-of-deletions’, we find something interesting.

Going back to this, so the cell $[0,0]$ holds the cost for going from the empty string to the empty string.

The cell $[0, 1]$ holds the cost for going from user_string=”C” to goal_string=””, which is 1 because the user 1 ‘insertion’.

The cell $[1, 0]$ holds the cost for going from user_string=”” to goal_string=”C”, which is 1 because it cost 1 ‘deletion’.

The algorithm

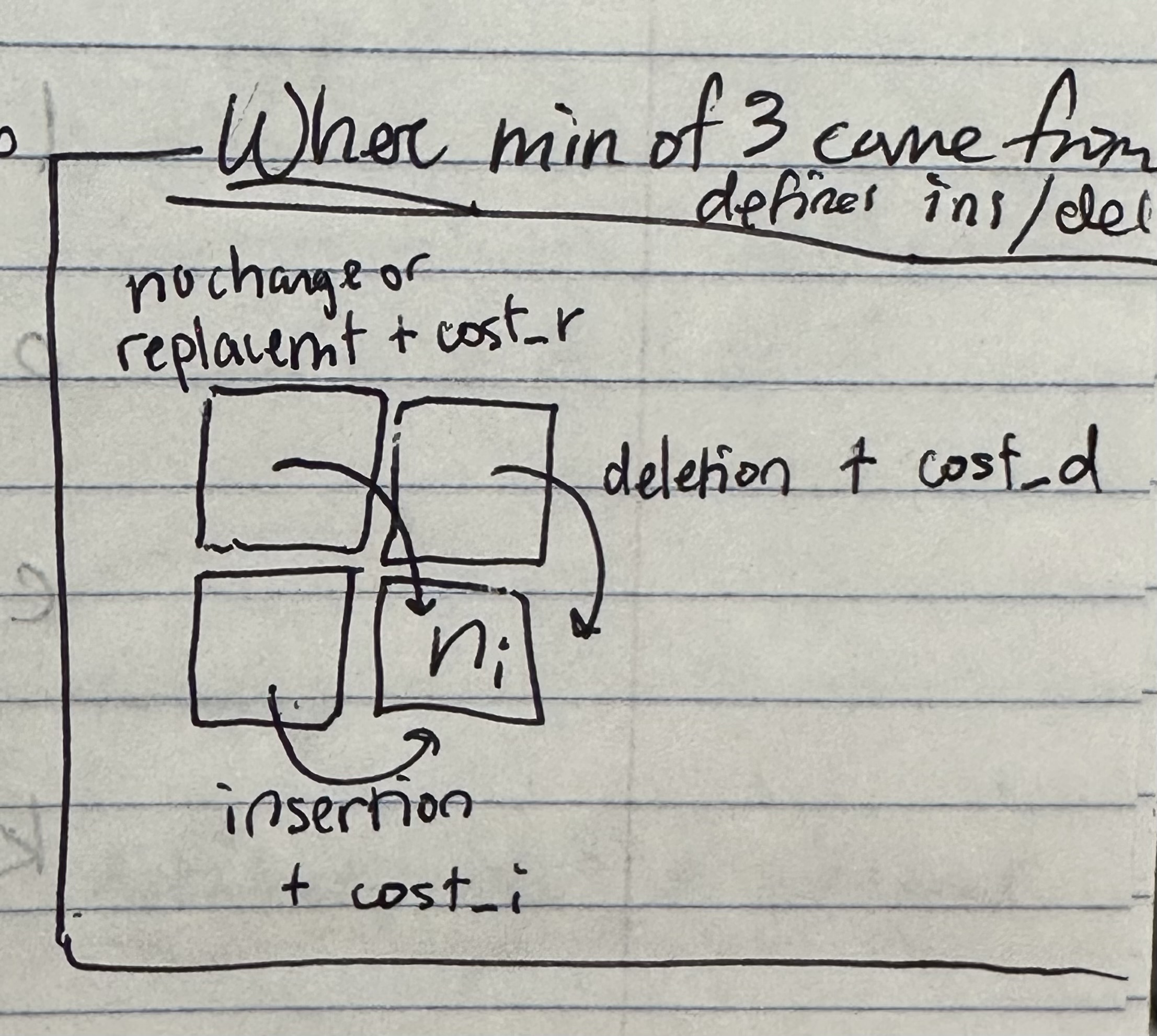

Now iterate through the rest of the cells in the matrix. At each step we have 4 options, each corresponding to a specific operation.

It turns out that if we just take the minimum value of the 3 cells directly adjacent and to the left of the current cell, then we can associate each with a specific non-identity operation.

If the two letters corresponding to the indices for the cell are different….

- If the min-of-three comes from the left, then it’s an insertion, kind of like the ‘lots-of-insertions’ example.

- If it comes from the top, it’s a deletion, like the ‘lots-of-deletions’ example.

- If it comes from the diagonal, it’s a replacement. So we don’t need to insert or delete. And then we add +1 to the cost to account for the new operation, and then put that in the matrix at the location.

In the special case where the two letters are the same, then we treat it as a ‘no-insertion’ and ‘no-deletion’ operation and take the cost from the diagonal.

Result

So after filling in the entire matrix with the cost information, we can get the non-truncated, honest-to-goodness string edit distance between the two full strings.

We got a final cost of 2! Which makes sense given that we only need two operations

- replacing the L with O

- deleting the last C to fully transform CLOCK into COOK.

Leave a comment