A gentle introduction to the MOSES algorithm

Ganglab - Fall 2024

This past summer, I started working with the Gang Lab at Columbia University as a chemical engineering research assistant. I received a generous grant through both the CCE and WEP programs which allowed me to stay in New York over the summer. I thus began conducting research with Jason Kahn, a former member of Gang Lab and now full-time materials scientist at Brookhaven.

I was fortunate enough to receive another funding award from WEP to help fund my continued research with Gang Lab into the semester. As part of the program, I am writing a series of blog posts about my experience working in the lab.

Since I have already been working with them for 4 months at this point, the problems I’m now working on require some background to understand. I wanted to dedicate the rest of this first post to explaining the bare essentials of the problem Jason and I are trying to solve.

My project: MOSES, the coloring algorithm

Despite the Gang Lab being foremost a chemical engineering research lab, I joined as a programmer - with the task of rewriting Jason’s 2000 line jupyter notebook containing the previous iteration of a “DNA origami coloring algorithm.”

The physical + chemical properties of how and why this system actually works is a very long discussion, one that my limited physics background as a CS major is ill-equipped to handle. Rather, I want to introduce the problem to you at its bare essentials and give a high level overview of what our algorithm is trying to do.

The building blocks of DNA origami

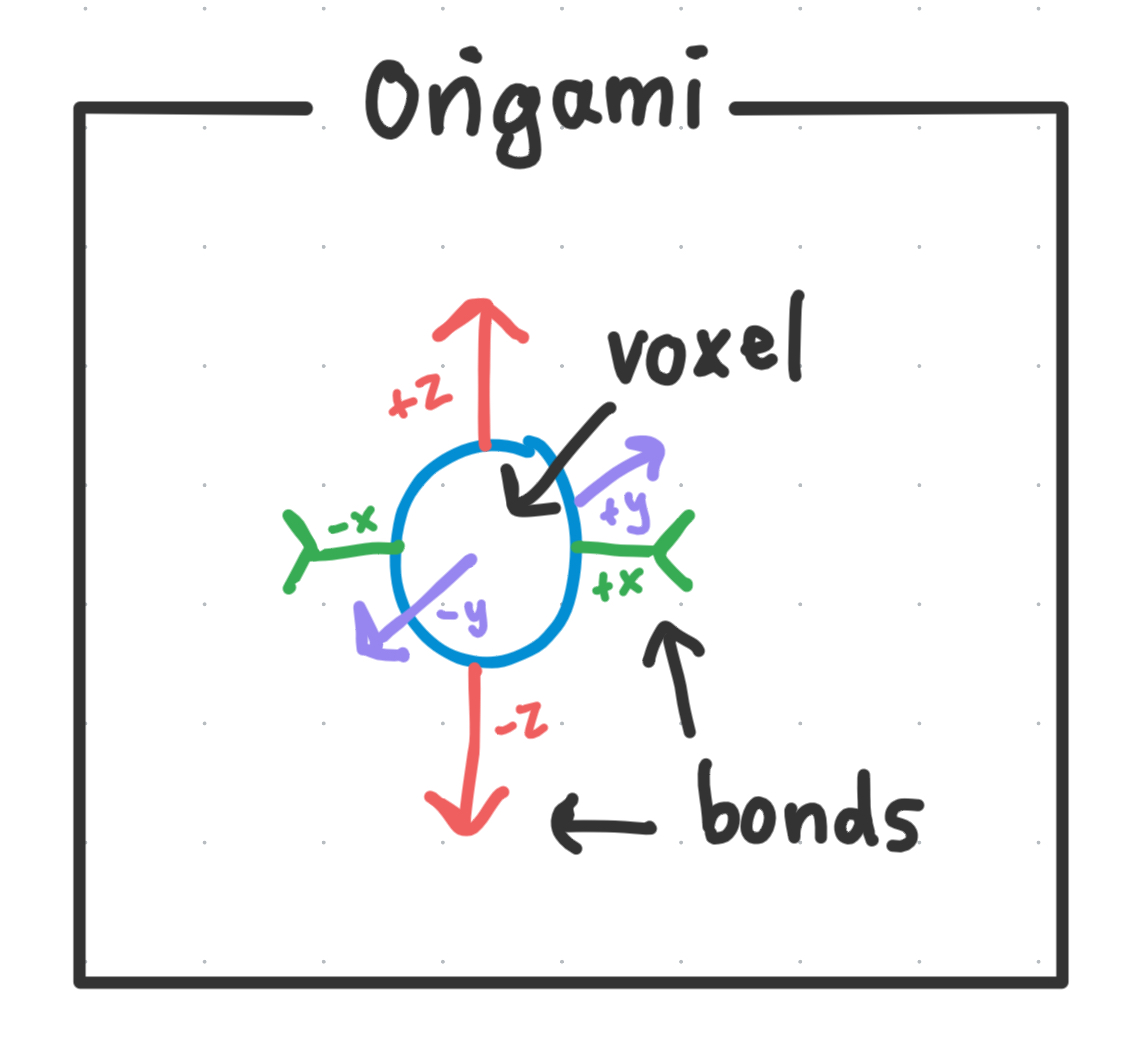

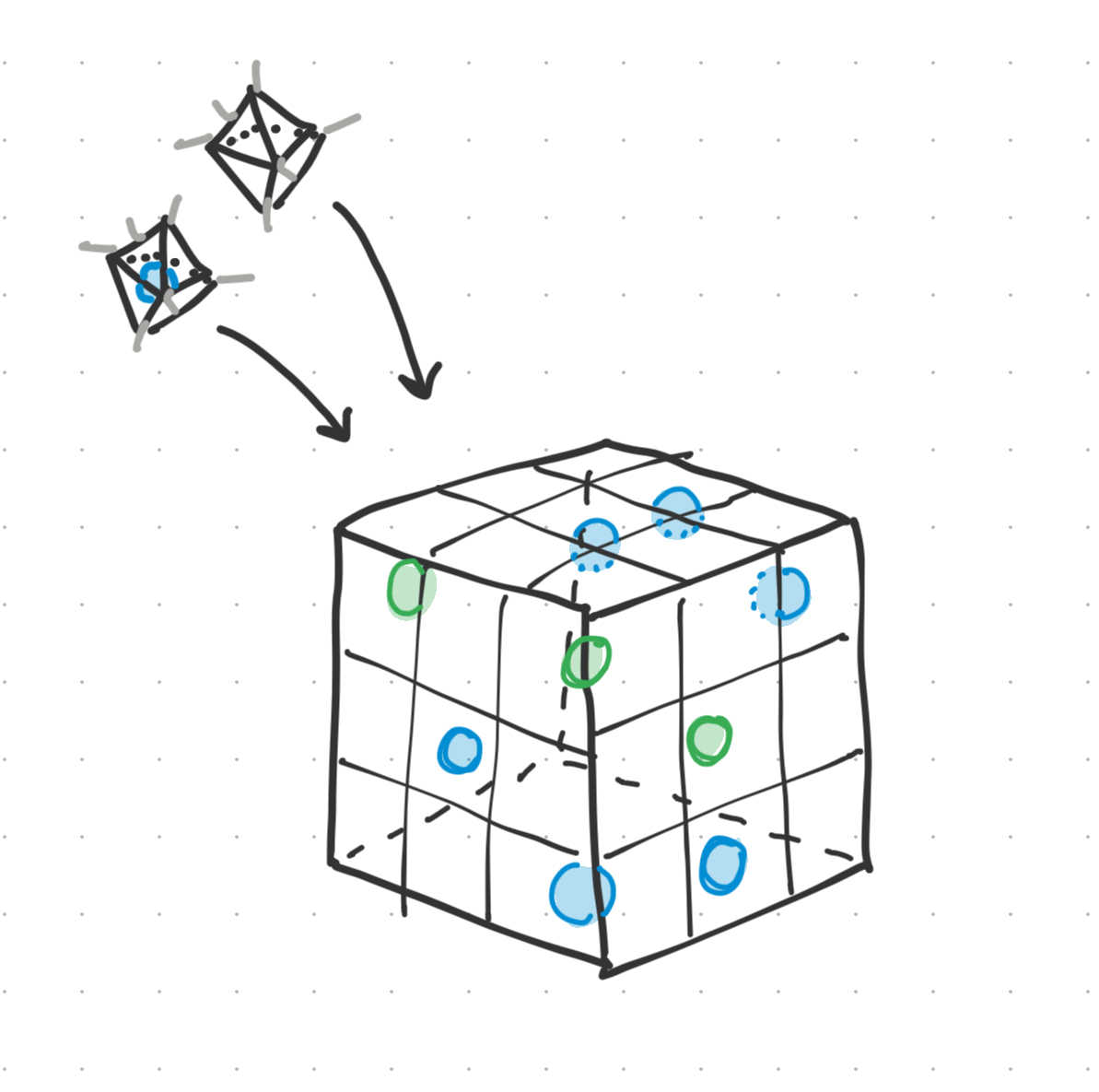

The term DNA origami refers to name for the basic building block of our system.

It is a structure consisting of a voxel and a set of bonds.

Voxel

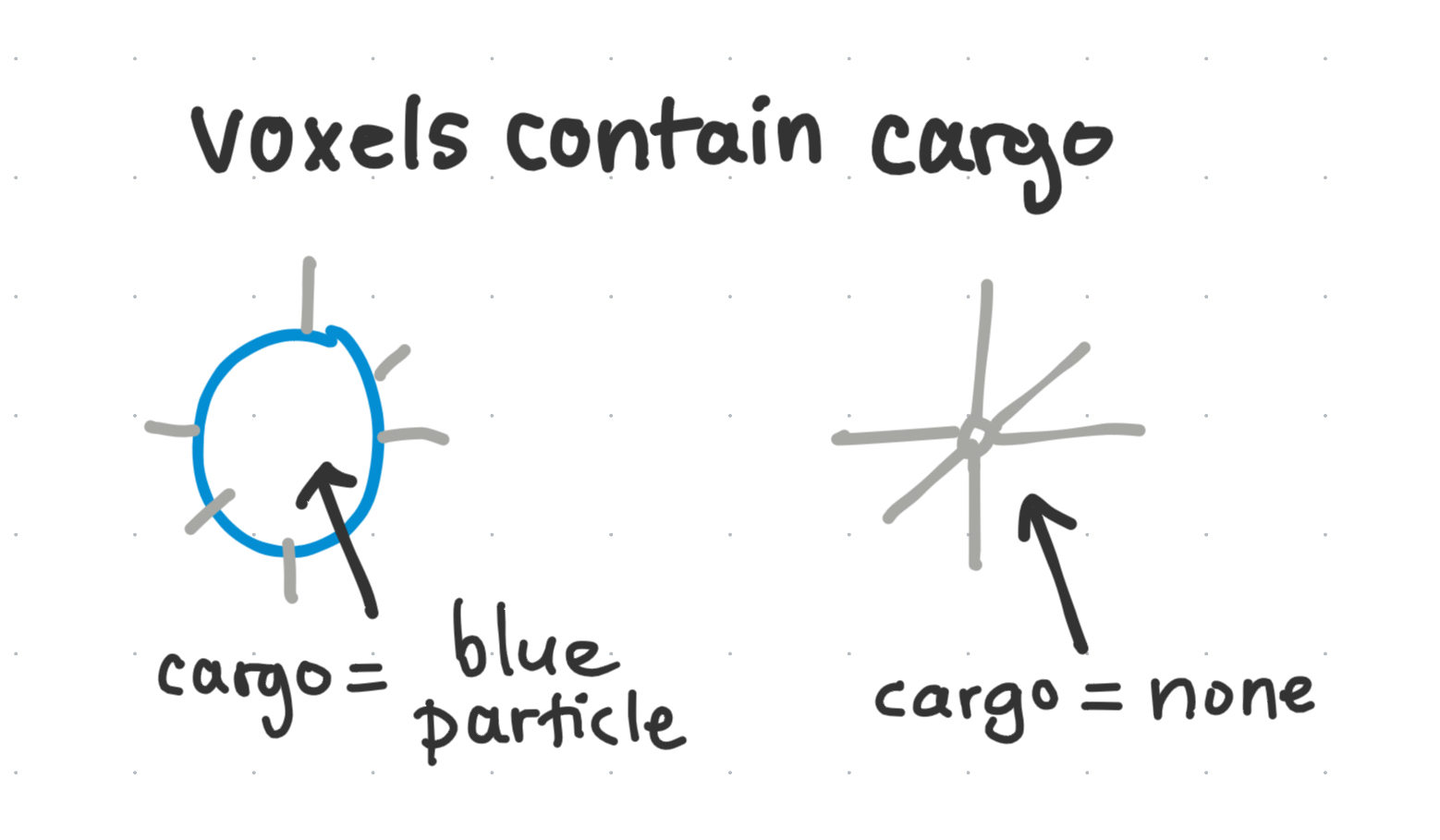

The “voxel” (which borrows its name from the computer graphics voxel) is a vessel that can store either a choice of particle inside, or no particle at all. It is like the ‘vertex’ in a graph.

Bonds

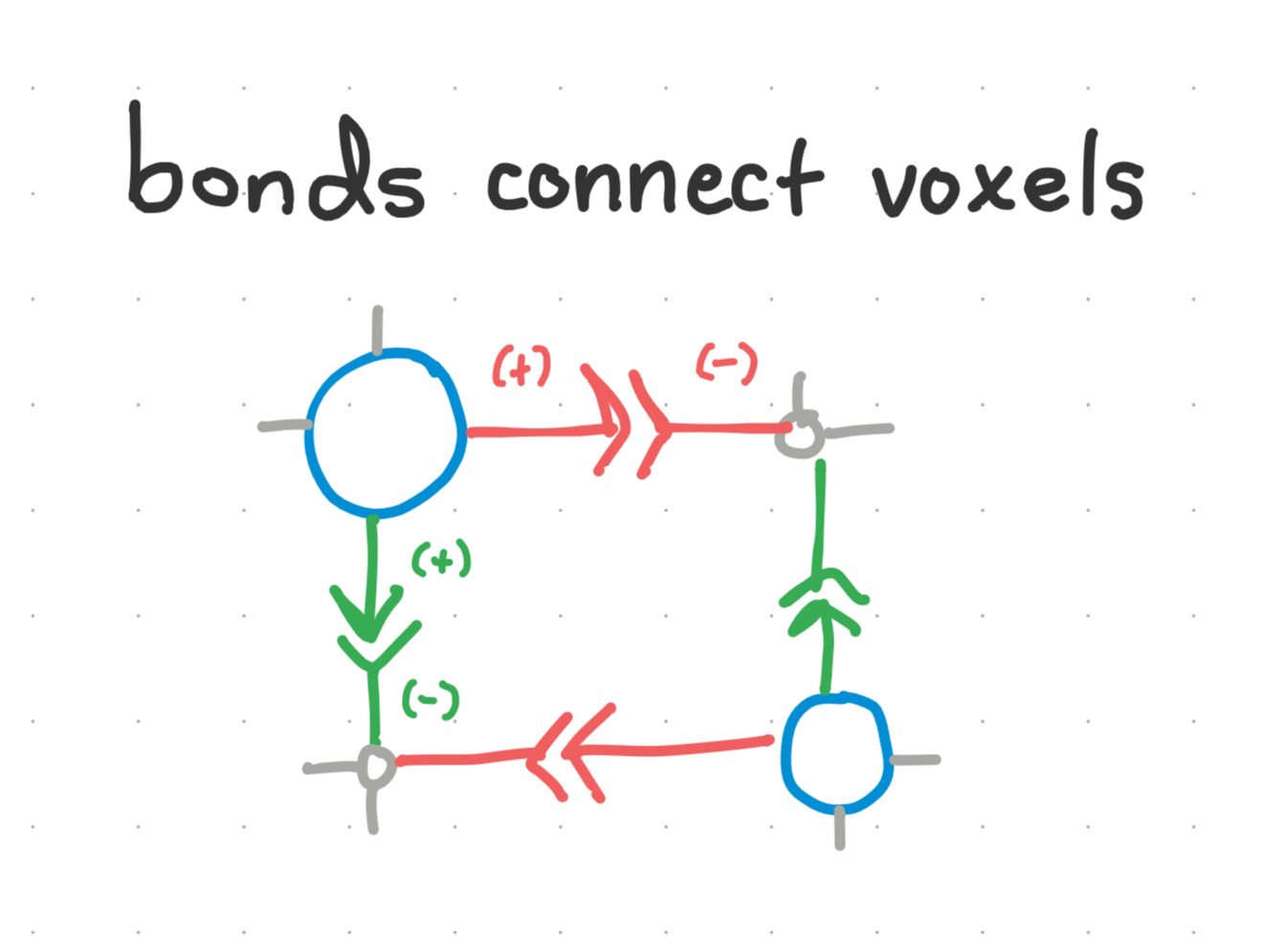

It is attached to 6 bonds on the +/- x, y, z vertices* of the voxel, which connects the voxel to other voxels.

- Note*: The voxel is actually an abstraction for an octahedral DNA wireframe, which contains 6 distinct vertices for the bonds to stick out from. This is also why it is called DNA origami.

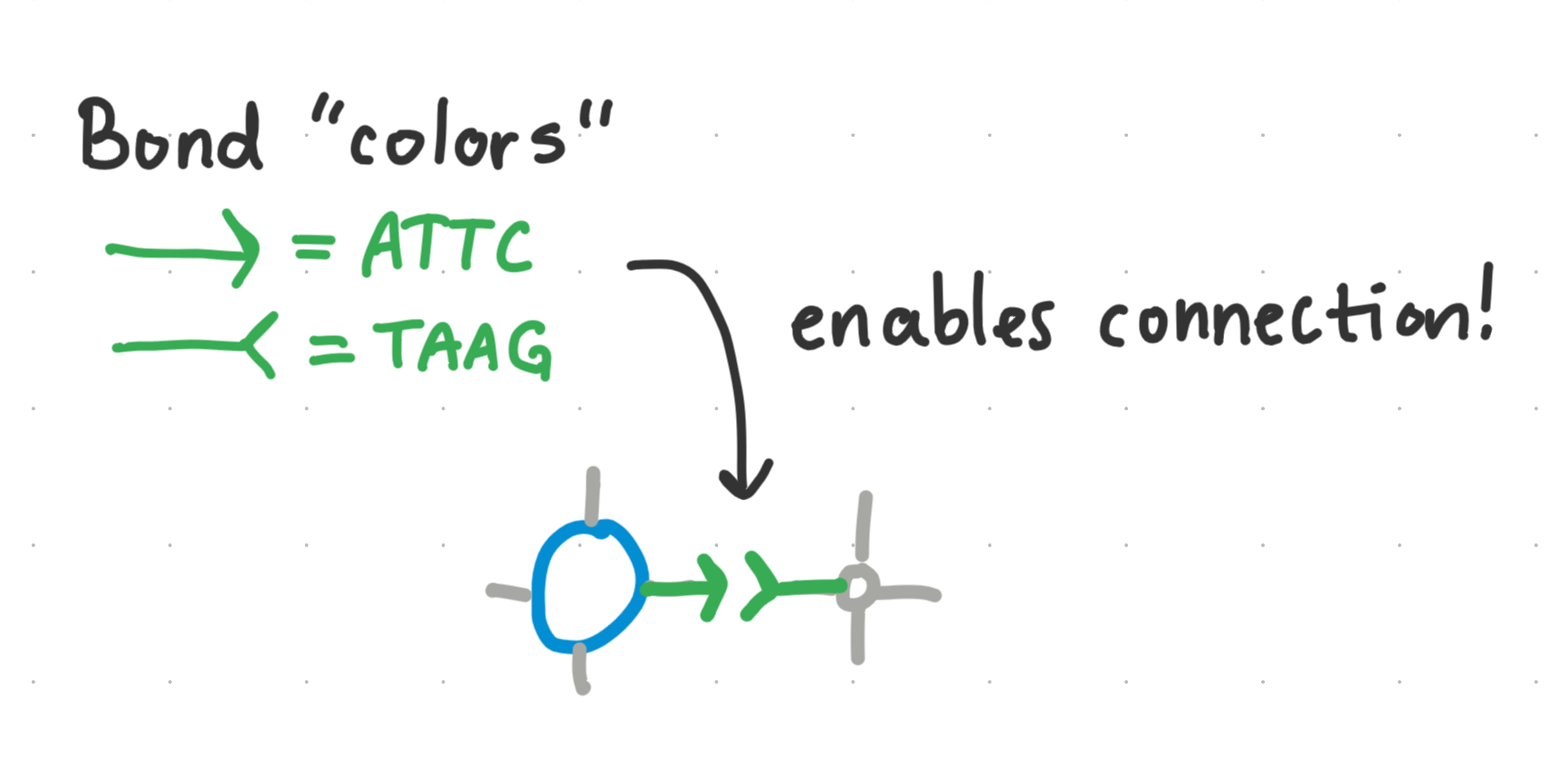

Each bond has an associated color - and each color has its complementary color, which we denote with + / -. A voxel with a bond can only connect to another bond if they have colors of opposing complementarity…

These are like colored ‘edges’ in a graph coloring problem, where a color must connect to its complementary color.

Bonds connect to each other with the following binding rules:

- A bond can only connect to another bond with its opposing complementarity

- No palindromes: A color and its complement cannot exist on the same voxel

Structures: Lattices

The structures we ultimately build with these origami building blocks, are these superlattice particle structures. In 3D space, the origami come together almost like a Minecraft build.

It being a superlattice structure means that essentially, we have a minimum unique design which is copy-pasted infinitely around itself.

The problem: Bond coloring

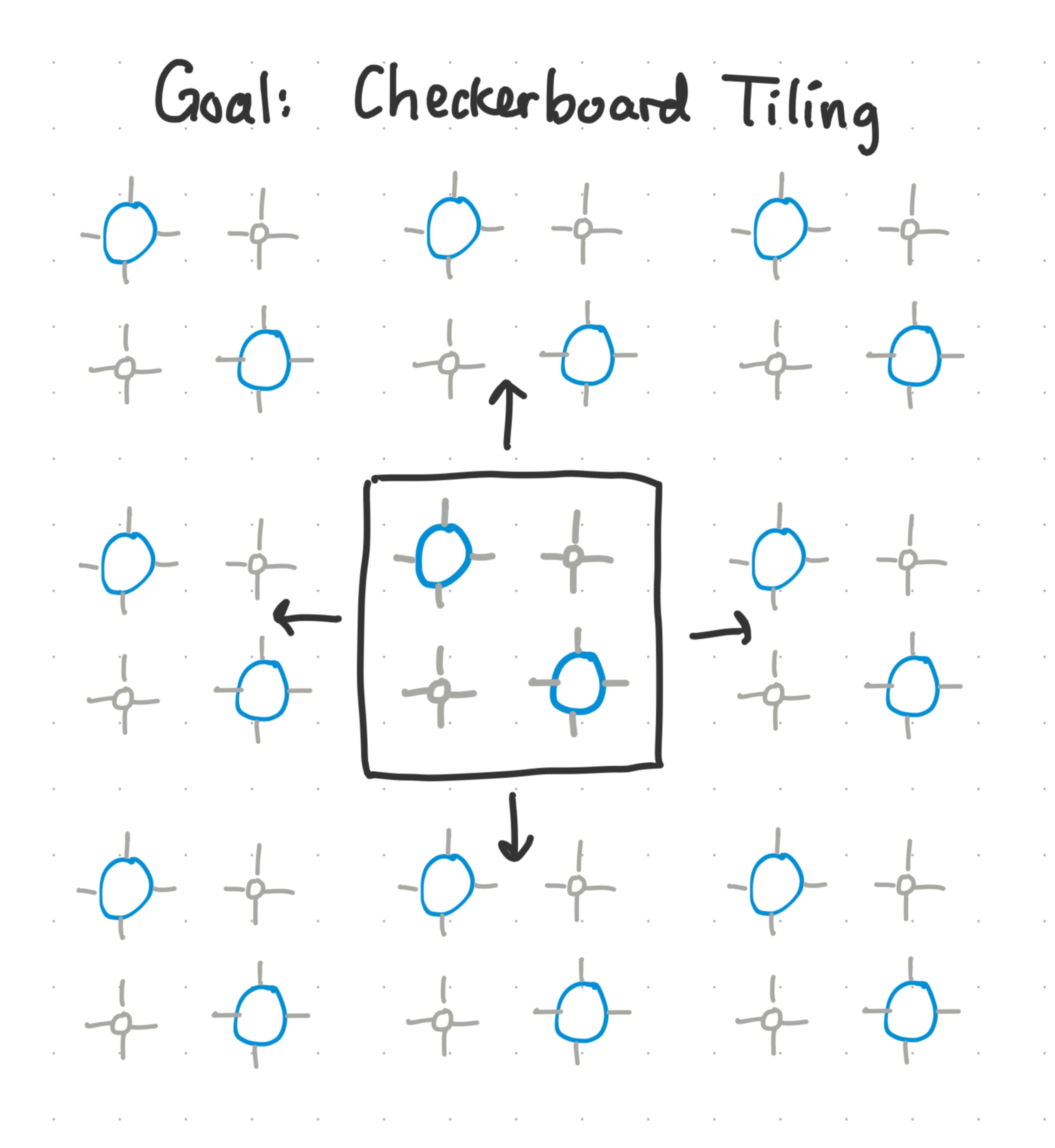

To simplify things for a bit, let’s step back to a 2D picture of what’s going on. Say we want to create the following 2D pattern which will tile out to infinity.

We know we want the particles to form this checkerboard structure. The question is, how do we design the colors of each bond, so that when we stick these origami into a machine and shake them around, that the complementary bonds come together and enable the origami self-assemble into our desired tiling lattice structure?

Naive solution

We could assume a naive solution is to paint each bond in the minimal design a different color. This ensures there’s no mistakes and each particle will end up where it needs to go.

However, the more colors it takes to create a certain design, the less likely it is to form. Hence, we have the criteria:

- less colors = better

- more colors = worse which forms the main motivation and constraint for our algorithm.

Keeping in mind the binding rules, how can we start to simplify the number of colors needed to ensure this design will still form as it should?

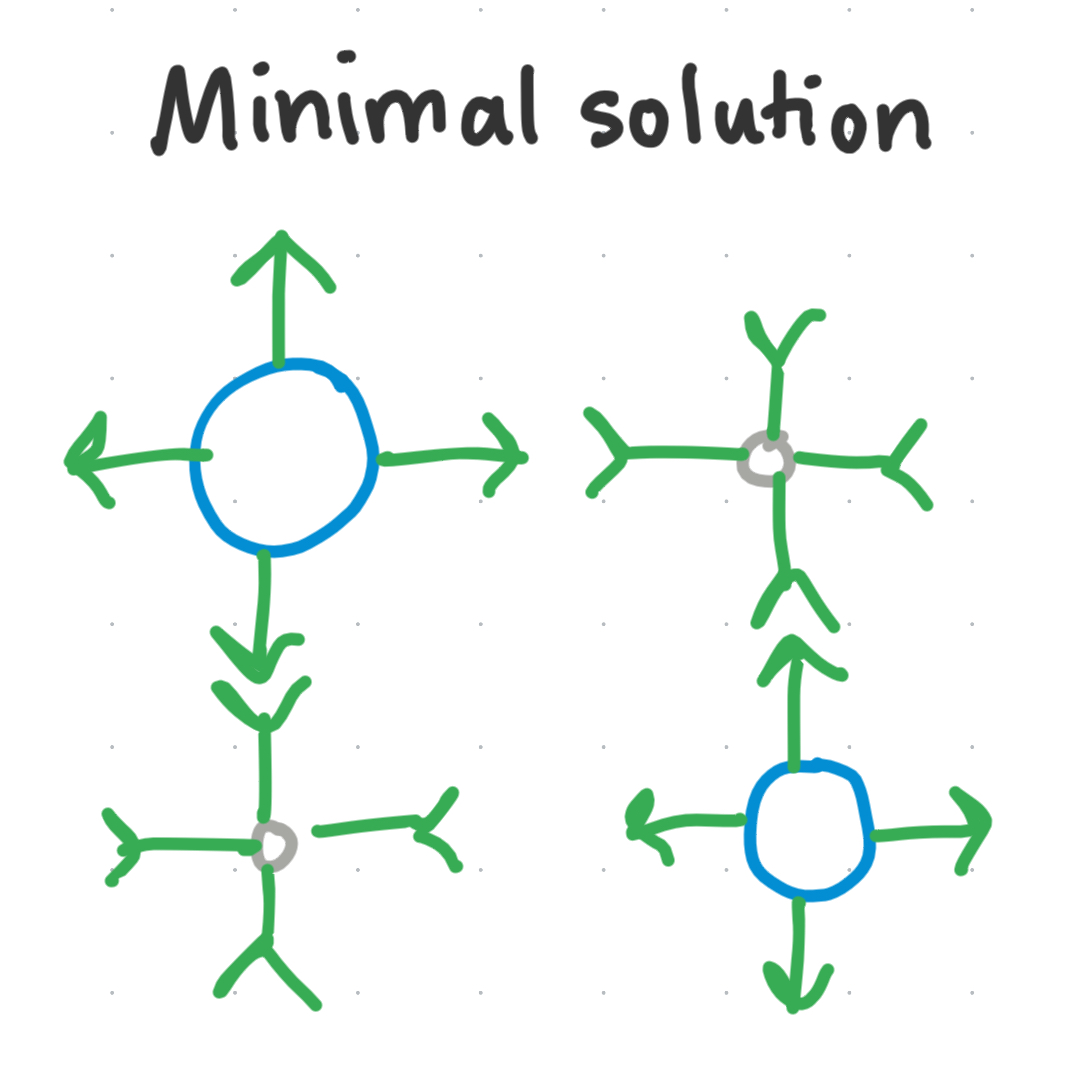

Minimal solution

It turns out, for this system we only need one color (+ its complement!)

For simple designs like this, we can often reason out a minimal number of colors by hand. However, as we want to create more complicated 3D designs, it becomes much harder to do the computations by hand. Hence, our lab over time, slowly developed this algorithm which does it computationally.

Over the summer, I rewrote the entire codebase and created a GUI to visualize the voxels + bonds in the lattice structures.

Looking ahead: Fall 2024

There is still some work that needs to be done with debugging the coloring portion - we are looking to publish the algorithm as a paper soon, so making sure everything works as expected is of the top priority.

Next steps, we want to extend the codebase to algorithmically compute the ideal binding order (binding temperature) for each bond in the lattice.

Leave a comment