Explaining the Binding Library project

This semester, I was tasked with finishing up the binding library project for Dan Redeker, and packaging it into a user-friendly interface. This blog post aims to explain what exactly this project is, in the hopes of also conveying why I find it cool.

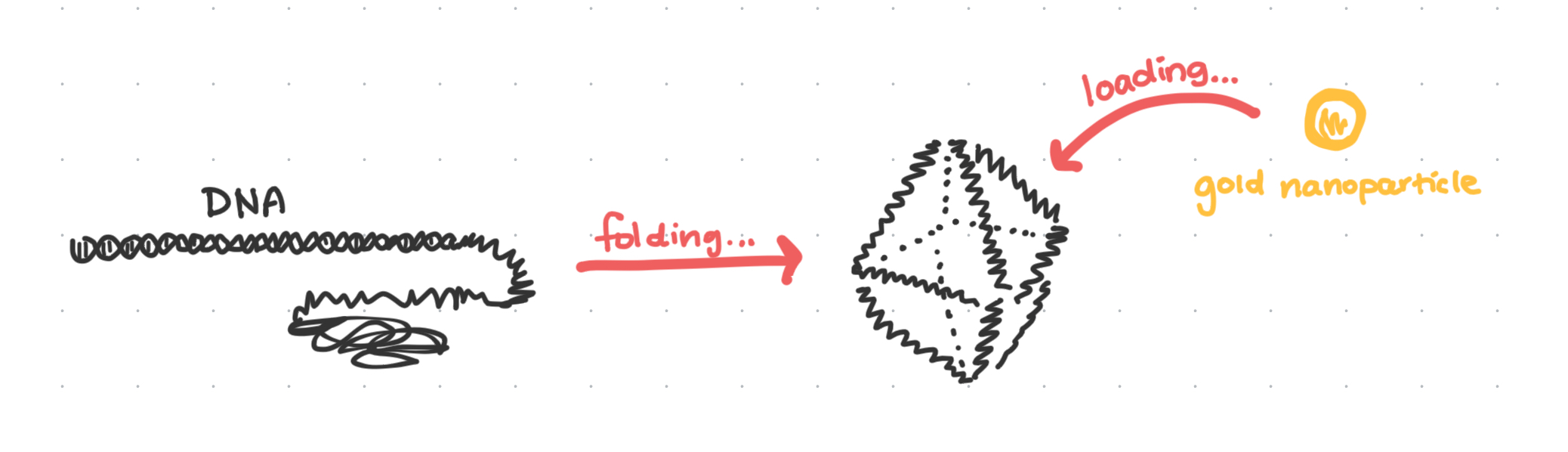

The setting: DNA origami

Some necessary prerequisite information about the Gang Lab: We are a material science research group, focused on a technique called “DNA origami.” The name comes from how we fold DNA into different shapes to form the basis of our nanomaterials.

The DNA origami voxel

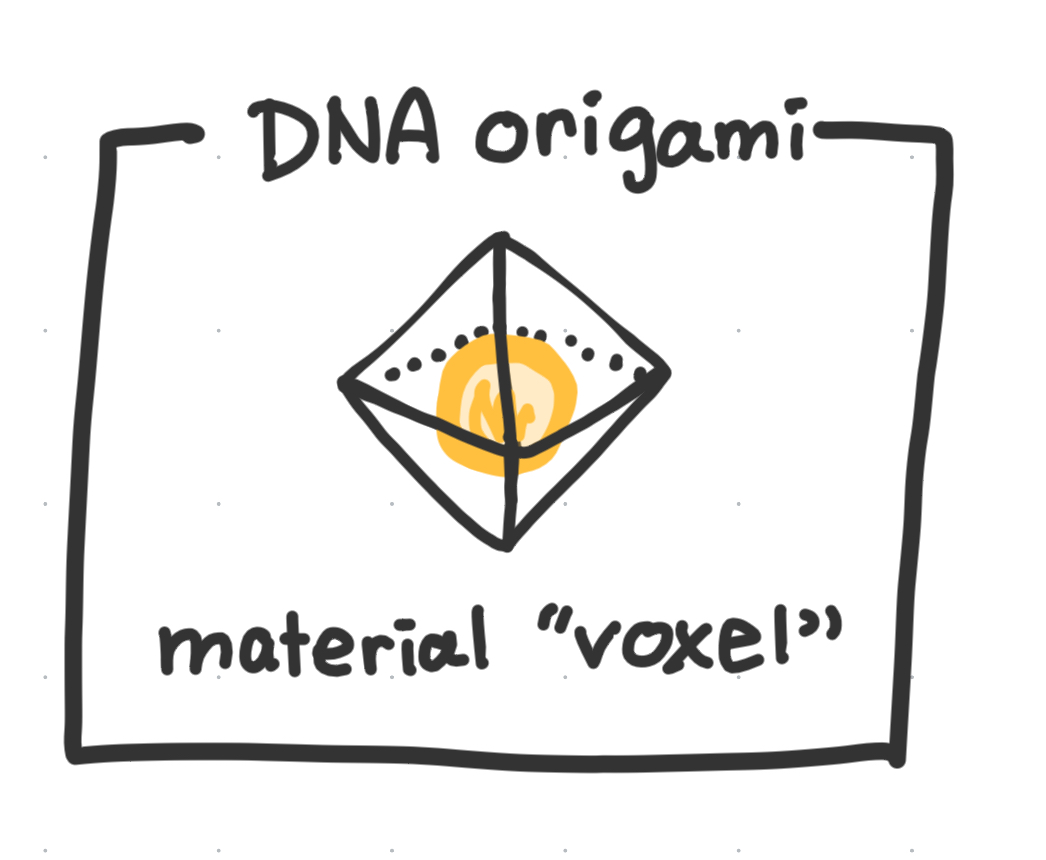

Our lab works a lot with octahedral and tetrahedral dna origami wireframes, which we can “load” with arbitrary nanoparticles like gold.

Self assembles into a lattice

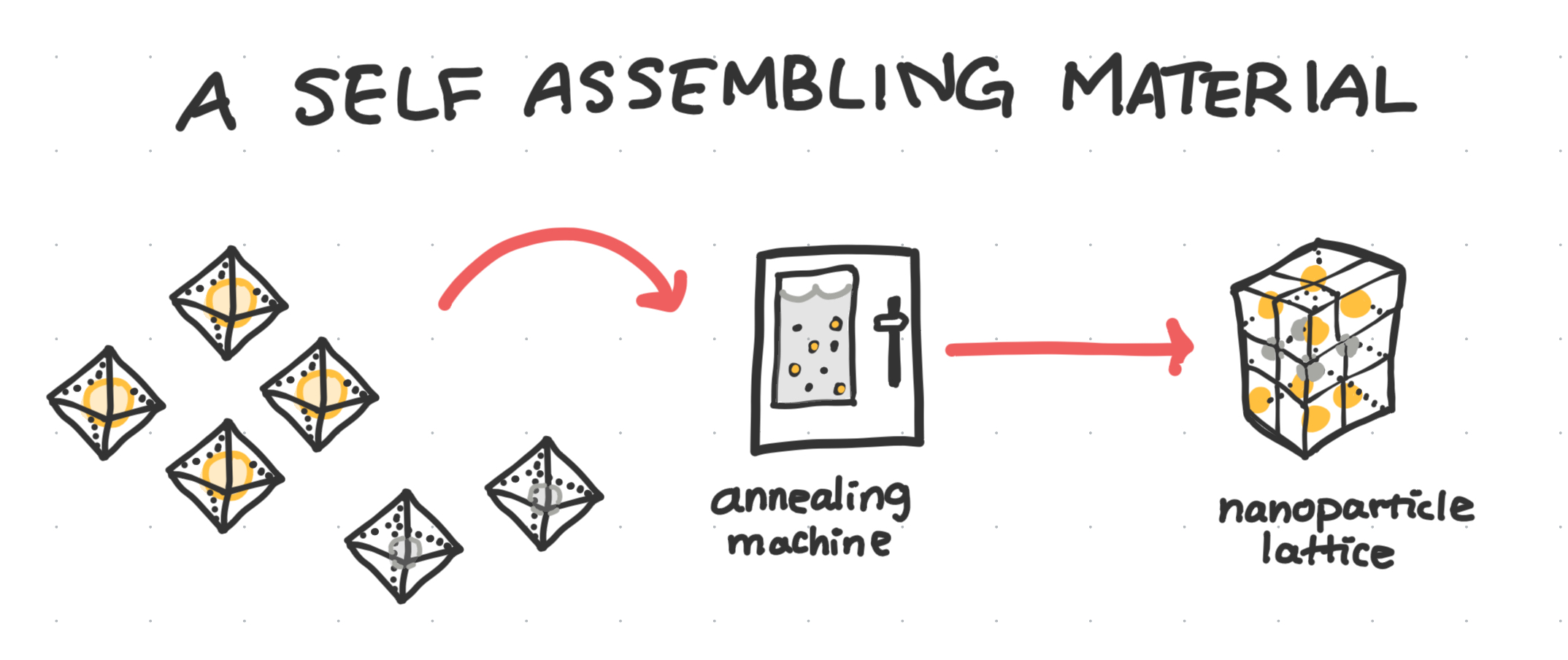

Dr. Gang’s work was influential in setting the foundations for the technique of using nanoparticle-loaded DNA origami as building blocks to create larger, tiling lattice structures.

With more DNA!

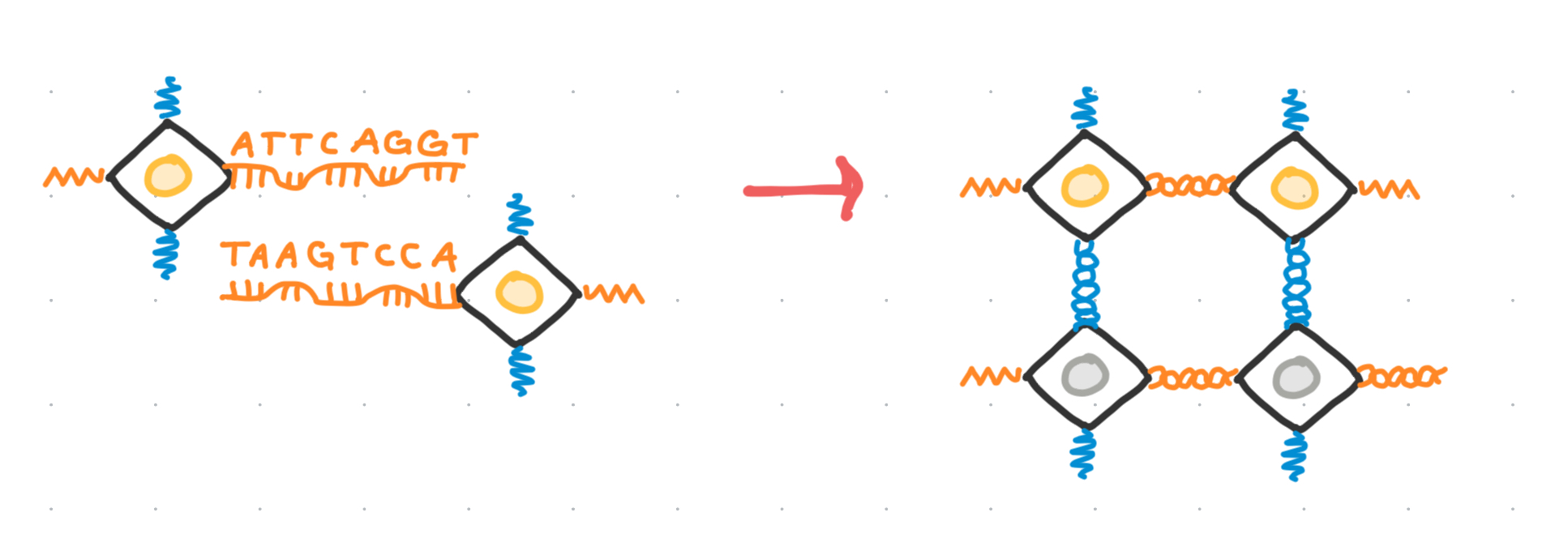

Notably, this self assembly is enabled through the use of single stranded DNA sticking out at the vertices of the octahedra. These are used to connect different building blocks together, and only at certain sides, such that the desired nanoparticle structure is achieved through self assembly.

These single stranded sequences, also called “sticky ends” or “bonds”, are often abstracted away with using a single color to represent strands of differing base pair content—strands which in theory should not bind together.

The problem

Structural binding errors

However, if too many of the base pairs overlap, there’s a chance that a voxel can bind in the wrong orientation, leading to the propagation of structural binding errors.

The problem statement

Dan Redeker’s Binding Library project aims to address this problem of cross-contamination: given a DNA sequence length of N base pairs, what is the maximum ‘library’ of different sequences we can draw colors from, such that no two sequences will bind to any other sequence in the library other than to its rightful complement?

Dan’s solution

The solution was surprisingly elegant.

Define orthogonal

First, a definition: Two sequences are “orthogonal” to each other if they contain no matching subsequence of over 4 base pairs.

The method

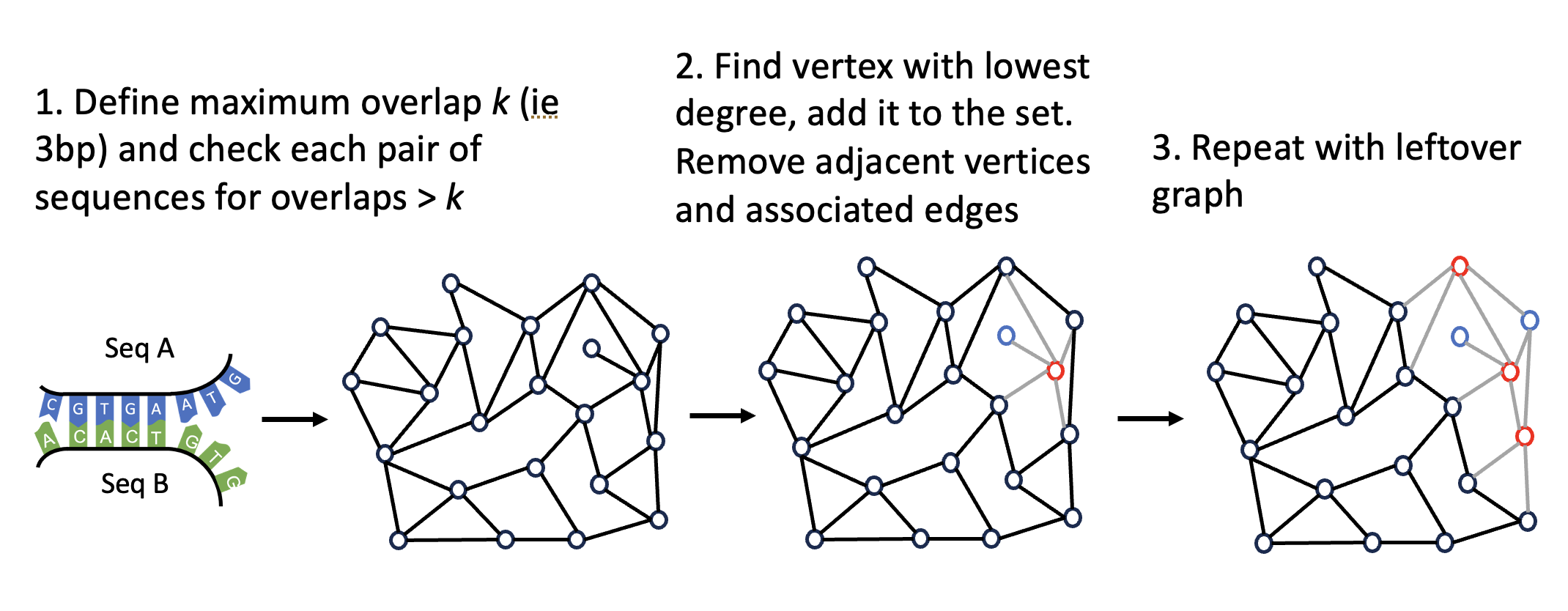

- Compute all possible DNA sequences of length 8

- e sort it two sets: A (color) and A’ (complementary) sequence spaces

- Compute all pairwise orthogonality between $A \times A$ and $A \times A’$ and store the two in a matrix.

- This becomes a ‘graph’, where the values are booleans (1, 0) representing whether two sequences are orthogonal (1) or not (0).

- Compute a third matrix containing the OR of the AA and AA’ matrices.

- This accounts for the fact that a sequence C which is orthogonal to A will correspond to a sequence C’ which is orthogonal to A’.

- Now apply a minimally connected graph algorithm.

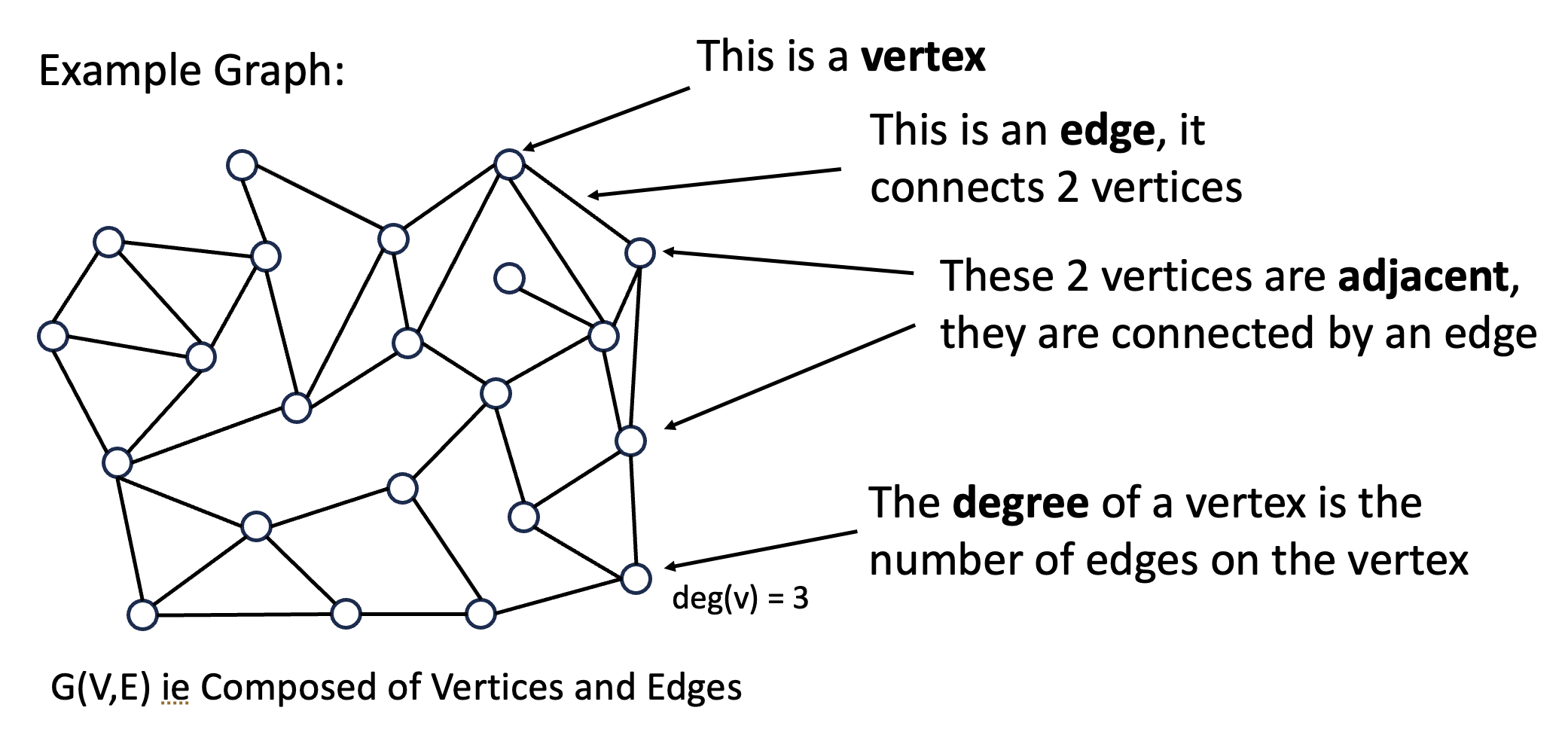

Rk: Graph theory definitions

The following images are from Dan’s beautiful presentation on the project. Notes:

- In this case, each “node” in the graph is a DNA sequence.

- Moreover, two nodes have an “edge” between them if they are orthogonal.

The minimally connected graph algorithm

Finally, the graph algorithm goes as follows:

While there exist nodes (vertices) in the graph…

- Find the node with the lowest degree

- Remove that node from the graph and place it into our library.

- Remove the neighbors which used to be connected to that node from the graph as well.

- Repeat until there are no nodes left.

The result is a library of “different-enough” DNA sequences (bonds) which we can use to connect our DNA origami lattices together.

Cool stuff!

Leave a comment